2016

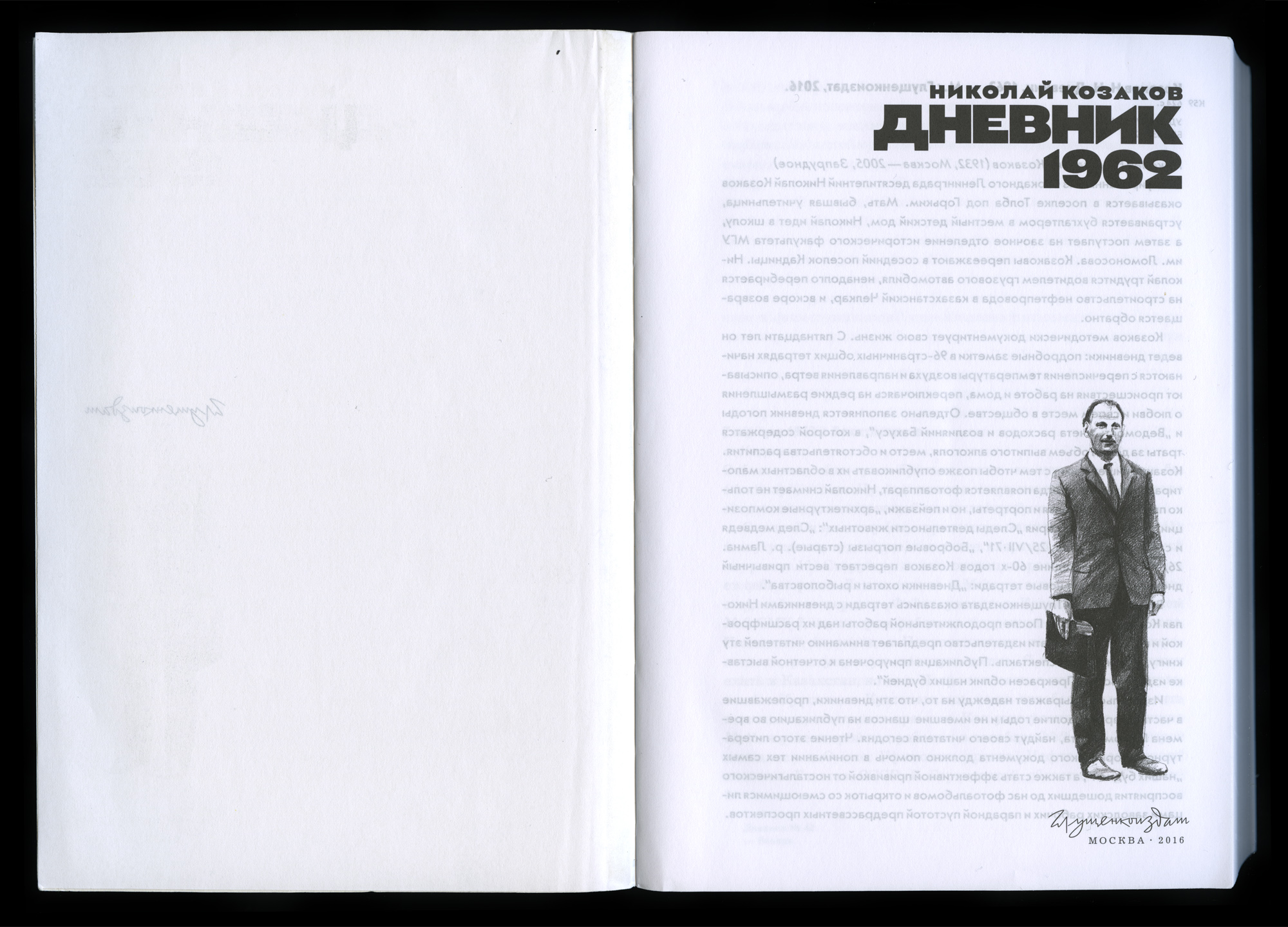

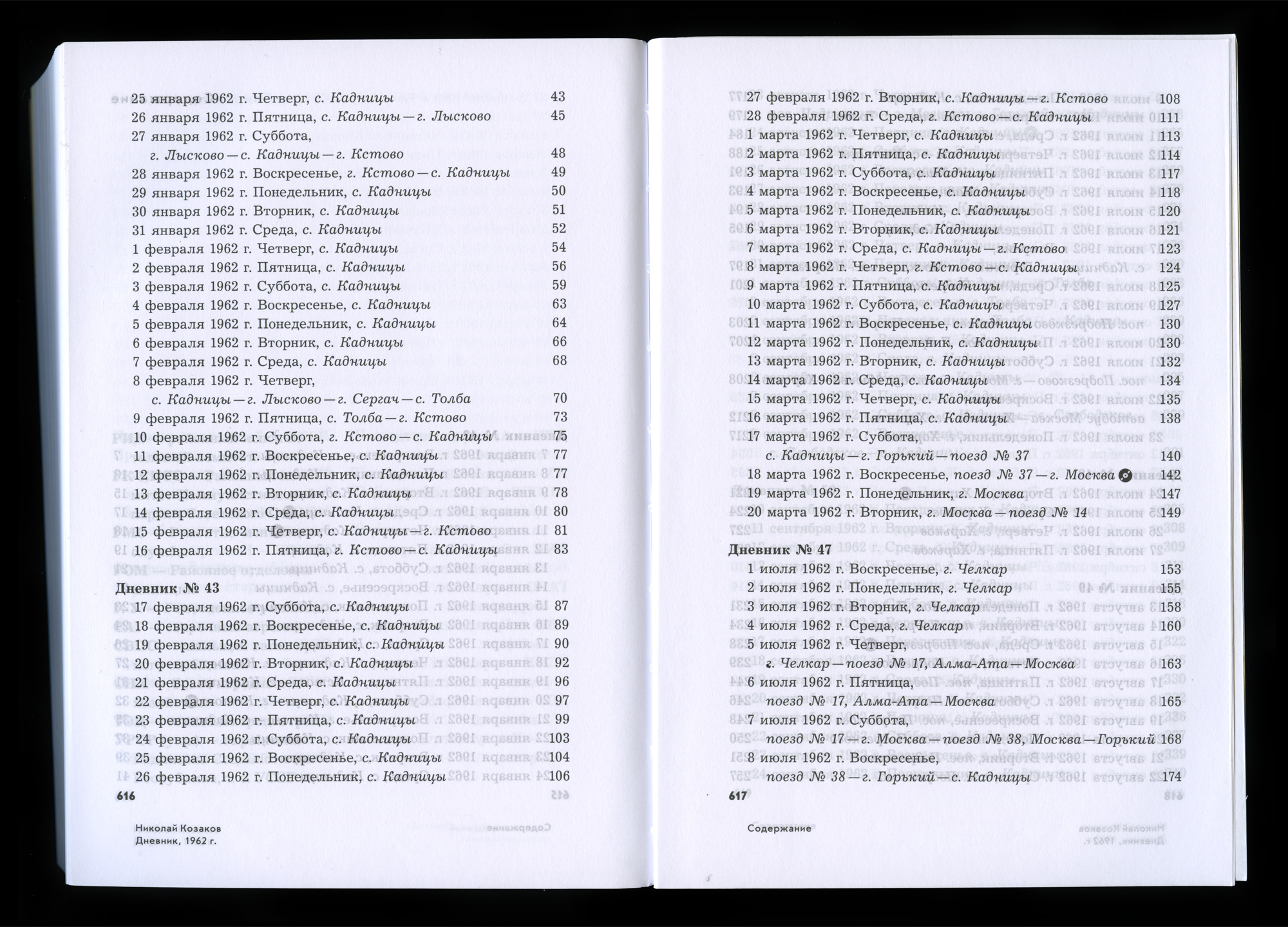

Nikolay Kozakov. ‘1962. Diaries’

№ 116 • Book

№ 116 • Book

← Fig. 1–6 →

2019

A Little Life

by Maria Kuvshinova

by Maria Kuvshinova

In “Trophimus,” a short story by Alexei Balabanov from the movie almanac “Trains Arriving” (1995), a peasant who had hacked his brother to death with an axe runs from his village to the city where, by chance, he is caught on film by cameras that a French associate of the Lumières had mounted on a train platform. One hundred years later, an assistant director working on the movie “The Train Stations of St. Petersburg” finds the old footage, but Trophimus—a creature whose onscreen agony lasted a full 20 minutes—is deemed an annoyance and winds up on the cutting room floor. Having lain in wait a full century for his chance to emerge from obscurity, when the moment finally arrives, he is merely cast aside. The camera, however, had been completely impartial, proving that it was even more humane than humans.

The exact opposite happened with the diaries of Nikolai Kozakov: thanks to human intervention, the text and its author were resurrected after death, like the miracle of the film footage that was spared. The immediate association with movies is no accident: the 1960s were the heyday of world cinema, and a time of outstanding prose scriptwriting in this country. Kazakov watches many movies and his perception and words are infused with film-like images in the same way as the writing of Hemingway or Dos Passos. He writes as though directly for the big screen: “I held up the musket, but the hare flashed among the pines. Vovka took a shot, and then we both took off after the hare. When I reached the clearing, the hare was already at least 100 yards off. I took aim. The grey-reddish fur ball was dancing in the crosshairs. My shot rang out. The hare jumped in the ravine, climbed out and ran up the hillside. I aimed again. My trigger made a clear click. My shoulder, ready for the recoil, had tensed for nothing.”

Unlike the fictional Trophimus, however, the real Kozakov has no interlocutor, witness, or interpreter to keep the author from slipping away again. In writing down his every step, he remains unknowable, like outer space—the conquest of which he devotes so much attention to in his notes. Who is he? A man of the ‘60s? An intellectual wretch? Your father’s older brother? Anti-Semite? Loser? Poet? Extraterrestrial? The diary is clearly not intended for anyone else to read: Kozakov writes it for himself and remains hermitically sealed within its text, exposing the reader to the principal and tragic impenetrability of “the Other.” Kozakov’s peculiar relationship with reality has no parallel in today’s world. It is like a message in a bottle that he sent not 50, but 500 years ago: he spends dozens of hours and days on communication, waiting for letters, for responses, for buses and trains, for public transport to be repaired, for road trips to end—the author describes territory with precious little connectedness (making it inhuman—but not because of any ideological hostility to man). The narrative line in his diary is broken and incomplete: we never find out why he writes all this, whether he ever sees his beloved Lilia Kantsedal of Kharkov again—we do not even understand the exact nature of his job, other than forever repairing his car and surmounting unpaved roads.

Only twice in 1962 did the whirlwind of events carry the author, like Gogol’s blacksmith, Vakula, from his humdrum provincial surroundings to wildly unanticipated worlds: to Moscow, where he converses in unexpectedly tolerable English with Americans dining at the Metropol restaurant, and later to Kharkov and the institute of the renowned Professor Dubrovsky, who fails to cure his stutter. Kozakov describes both journeys in the same dispassionate manner as he depicts the everyday life of Kadnitsy village. This makes them all the more fantastic, surprising, and cinematic to the reader and puts into relief the place that the author defines for himself on the world map. It is as though Kozakov has no idea that he lives in a provincial village behind the Iron Curtain. He handily inserts English expressions into his text, watches Hollywood films, and draws no distinction between publishing his work in a local newspaper or a Moscow journal, joking that American whistle-blowing journalists will show up in the neighboring village at any moment.

Sealed off from the reader, he is open to himself and the larger world, remaining at the same time a little man, a nobody—someone who should not bear witness, but does anyway. Stung by women, he does not attempt to establish patriarchal authority over them. Just the opposite: fleeing the claims of his ex-wife, Kozakov is ready to declare himself impotent, thus effortlessly removing himself from the domination game. His existence is so monotonous and uneventful that it devolves into an impersonal and non-descript existence—and it is this aspect (and not the hundreds of amazing details) that draws the reader in, as would an abyss.

The exact opposite happened with the diaries of Nikolai Kozakov: thanks to human intervention, the text and its author were resurrected after death, like the miracle of the film footage that was spared. The immediate association with movies is no accident: the 1960s were the heyday of world cinema, and a time of outstanding prose scriptwriting in this country. Kazakov watches many movies and his perception and words are infused with film-like images in the same way as the writing of Hemingway or Dos Passos. He writes as though directly for the big screen: “I held up the musket, but the hare flashed among the pines. Vovka took a shot, and then we both took off after the hare. When I reached the clearing, the hare was already at least 100 yards off. I took aim. The grey-reddish fur ball was dancing in the crosshairs. My shot rang out. The hare jumped in the ravine, climbed out and ran up the hillside. I aimed again. My trigger made a clear click. My shoulder, ready for the recoil, had tensed for nothing.”

Unlike the fictional Trophimus, however, the real Kozakov has no interlocutor, witness, or interpreter to keep the author from slipping away again. In writing down his every step, he remains unknowable, like outer space—the conquest of which he devotes so much attention to in his notes. Who is he? A man of the ‘60s? An intellectual wretch? Your father’s older brother? Anti-Semite? Loser? Poet? Extraterrestrial? The diary is clearly not intended for anyone else to read: Kozakov writes it for himself and remains hermitically sealed within its text, exposing the reader to the principal and tragic impenetrability of “the Other.” Kozakov’s peculiar relationship with reality has no parallel in today’s world. It is like a message in a bottle that he sent not 50, but 500 years ago: he spends dozens of hours and days on communication, waiting for letters, for responses, for buses and trains, for public transport to be repaired, for road trips to end—the author describes territory with precious little connectedness (making it inhuman—but not because of any ideological hostility to man). The narrative line in his diary is broken and incomplete: we never find out why he writes all this, whether he ever sees his beloved Lilia Kantsedal of Kharkov again—we do not even understand the exact nature of his job, other than forever repairing his car and surmounting unpaved roads.

Only twice in 1962 did the whirlwind of events carry the author, like Gogol’s blacksmith, Vakula, from his humdrum provincial surroundings to wildly unanticipated worlds: to Moscow, where he converses in unexpectedly tolerable English with Americans dining at the Metropol restaurant, and later to Kharkov and the institute of the renowned Professor Dubrovsky, who fails to cure his stutter. Kozakov describes both journeys in the same dispassionate manner as he depicts the everyday life of Kadnitsy village. This makes them all the more fantastic, surprising, and cinematic to the reader and puts into relief the place that the author defines for himself on the world map. It is as though Kozakov has no idea that he lives in a provincial village behind the Iron Curtain. He handily inserts English expressions into his text, watches Hollywood films, and draws no distinction between publishing his work in a local newspaper or a Moscow journal, joking that American whistle-blowing journalists will show up in the neighboring village at any moment.

Sealed off from the reader, he is open to himself and the larger world, remaining at the same time a little man, a nobody—someone who should not bear witness, but does anyway. Stung by women, he does not attempt to establish patriarchal authority over them. Just the opposite: fleeing the claims of his ex-wife, Kozakov is ready to declare himself impotent, thus effortlessly removing himself from the domination game. His existence is so monotonous and uneventful that it devolves into an impersonal and non-descript existence—and it is this aspect (and not the hundreds of amazing details) that draws the reader in, as would an abyss.