2017

Kirill Gluschenko

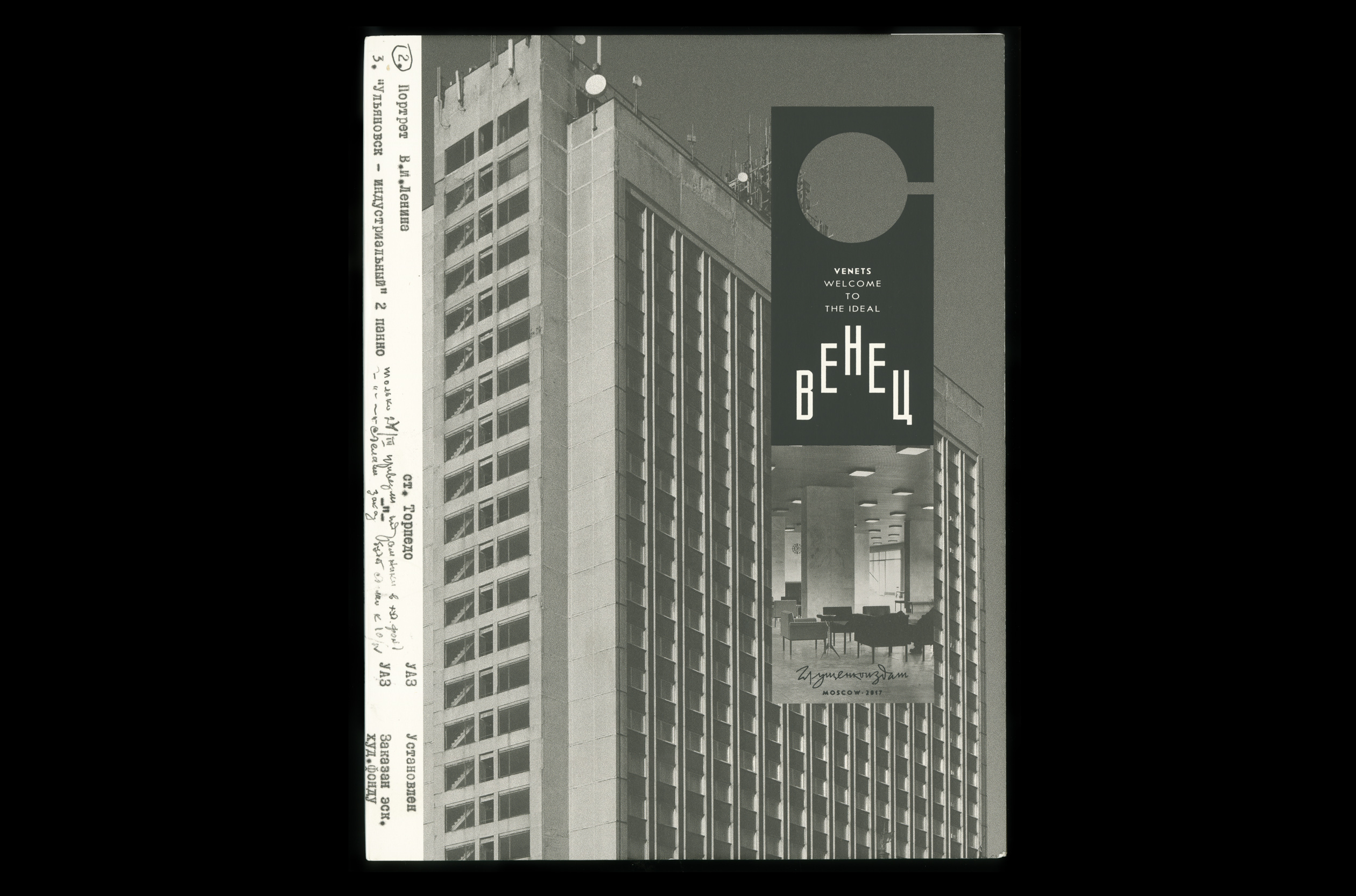

‘Venets’. Welcome to The Ideal

№ 150 • Book

‘Venets’. Welcome to The Ideal

№ 150 • Book

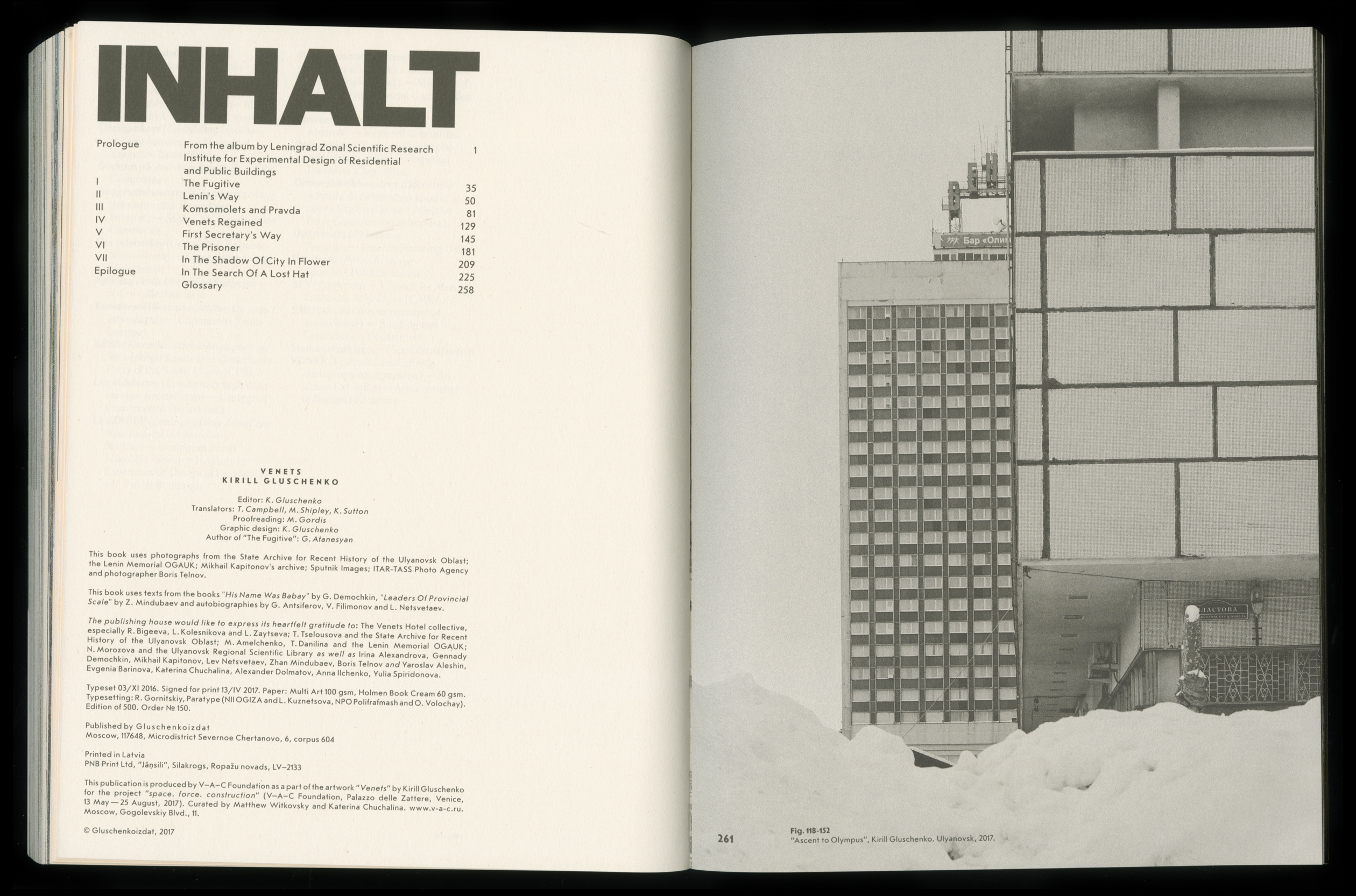

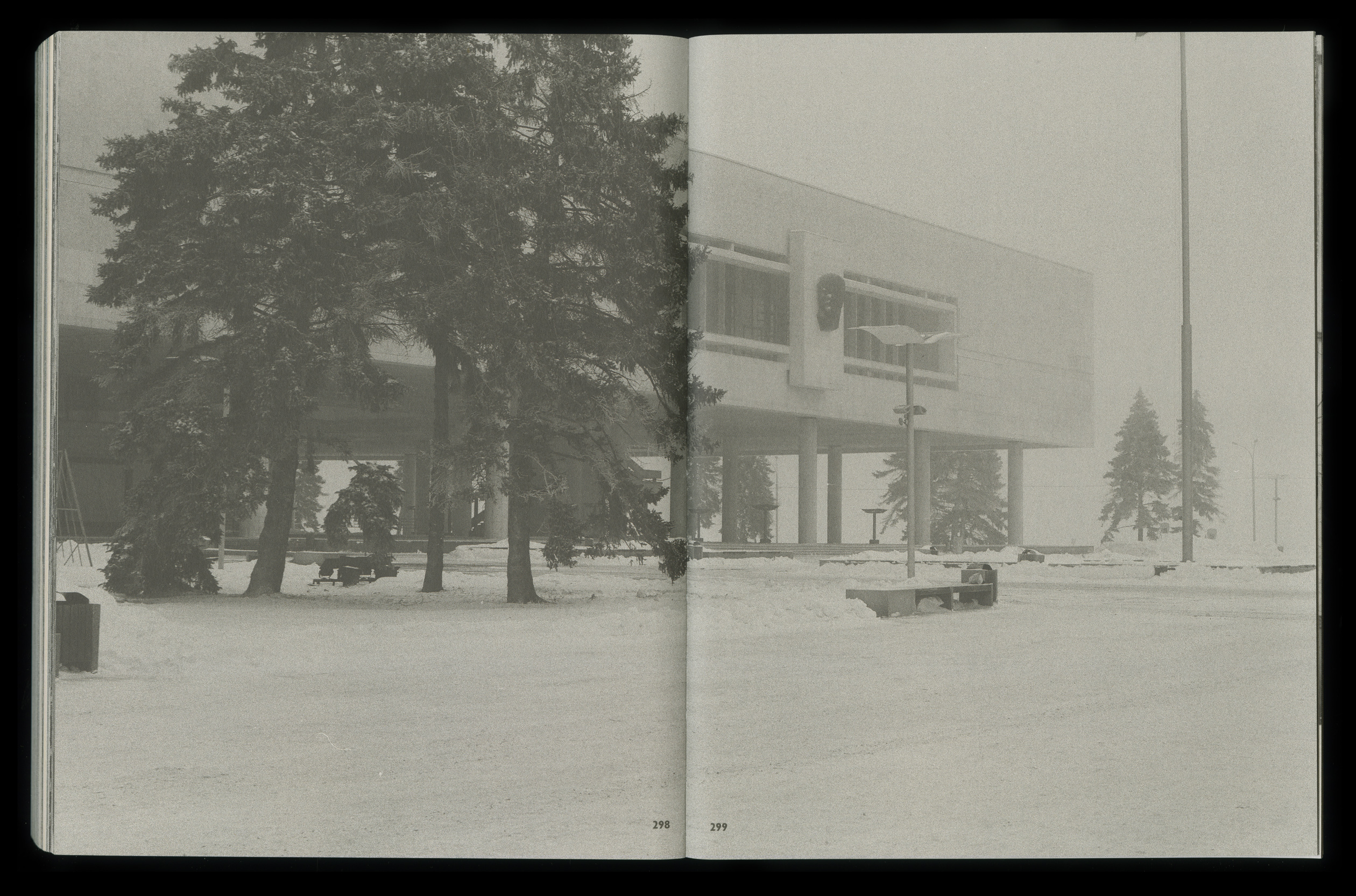

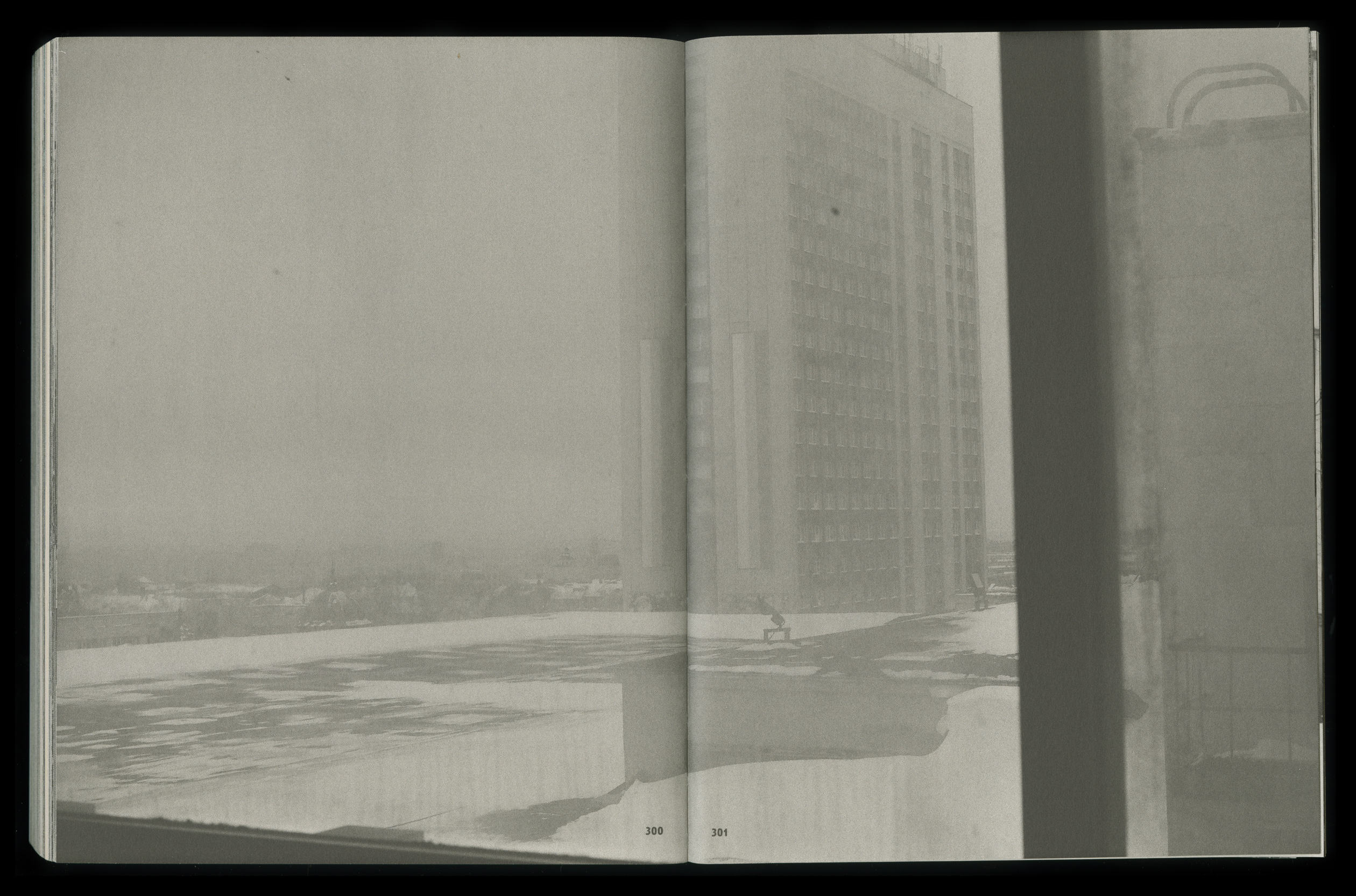

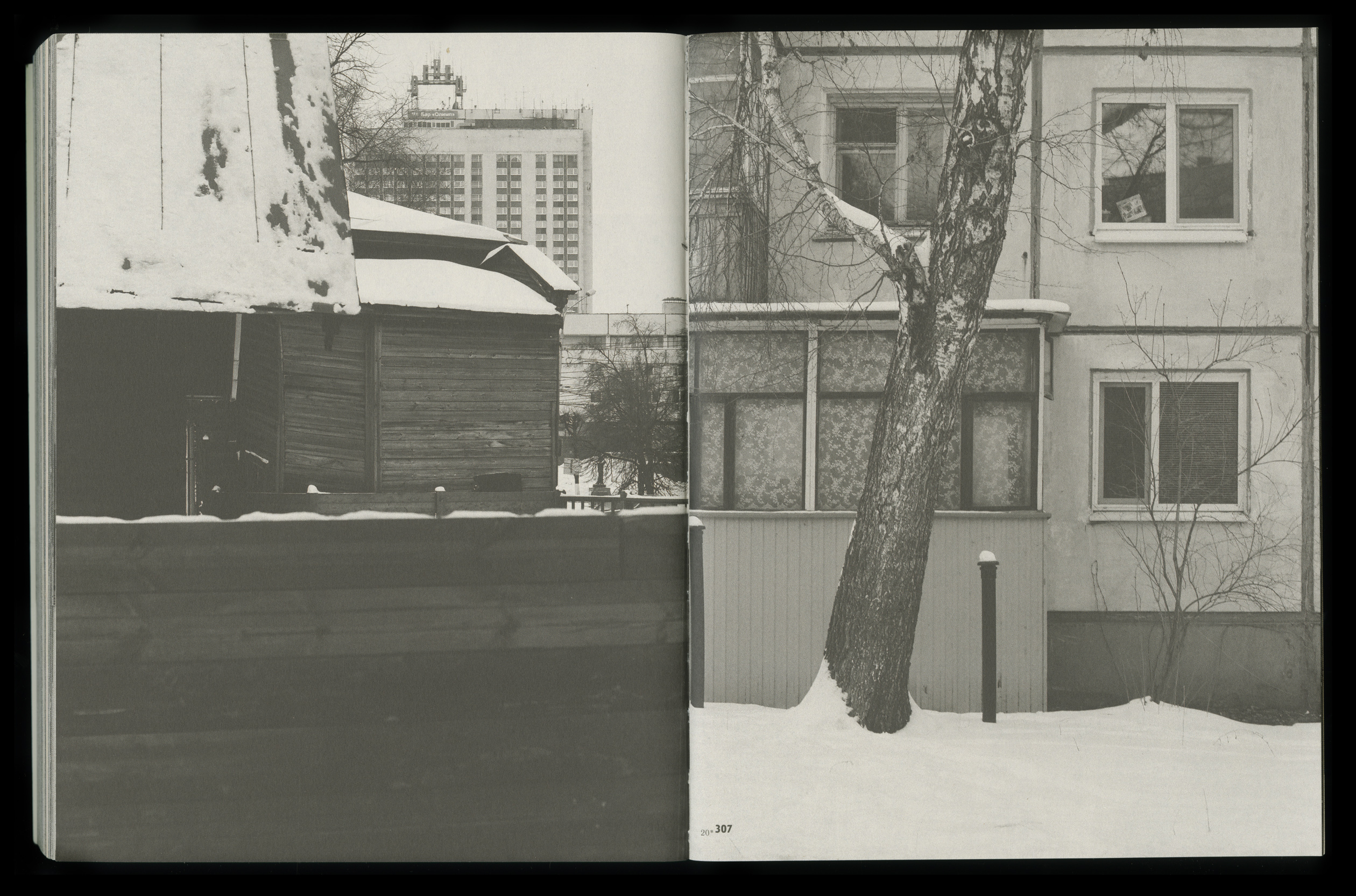

← Fig. 1–24 →

Order No. 150

ISBN 9–785990–951914

Softcover, 200 × 260 mm, 320 pages

500 copies. English

Gluschenkoizdat Press, 2017

€35 Order SOLD OUT

Editor: K. Gluschenko

Translators: T. Campbell, M. Shipley, K. Sutton

Proofreading: M. Gordis

Graphic design: K. Gluschenko

Author of “The Fugitive”: G. Atanesyan

ISBN 9–785990–951914

Softcover, 200 × 260 mm, 320 pages

500 copies. English

Gluschenkoizdat Press, 2017

€35 Order SOLD OUT

Editor: K. Gluschenko

Translators: T. Campbell, M. Shipley, K. Sutton

Proofreading: M. Gordis

Graphic design: K. Gluschenko

Author of “The Fugitive”: G. Atanesyan

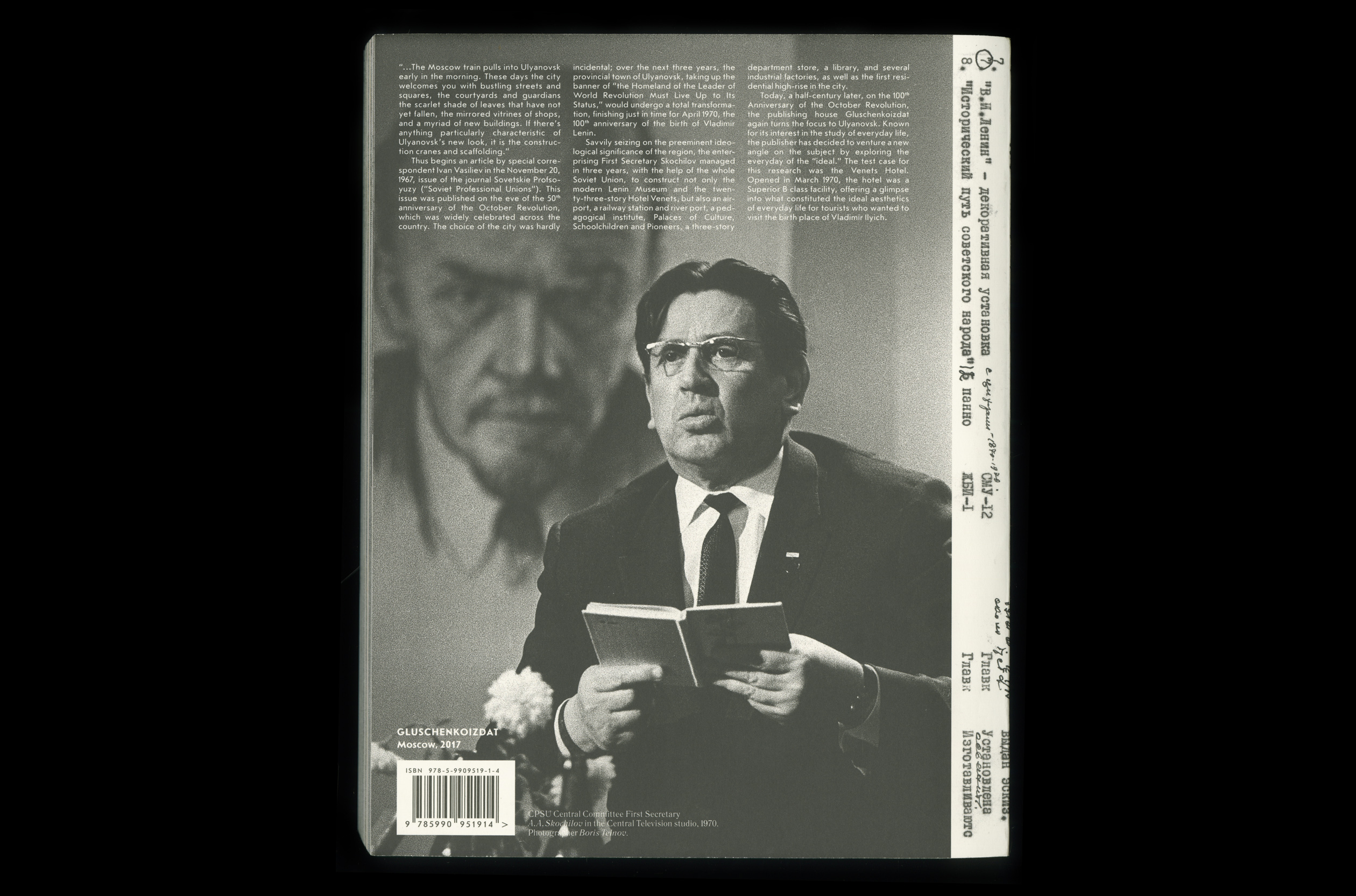

“…The Moscow train pulls into Ulyanovsk early in the morning. These days the city welcomes you with bustling streets and squares, the courtyards and guardians the scarlet shade of leaves that have not yet fallen, the mirrored vitrines of shops, and a myriad of new buildings. If there’s anything particularly characteristic of Ulyanovsk’s new look, it is the construction cranes and scaffolding.”

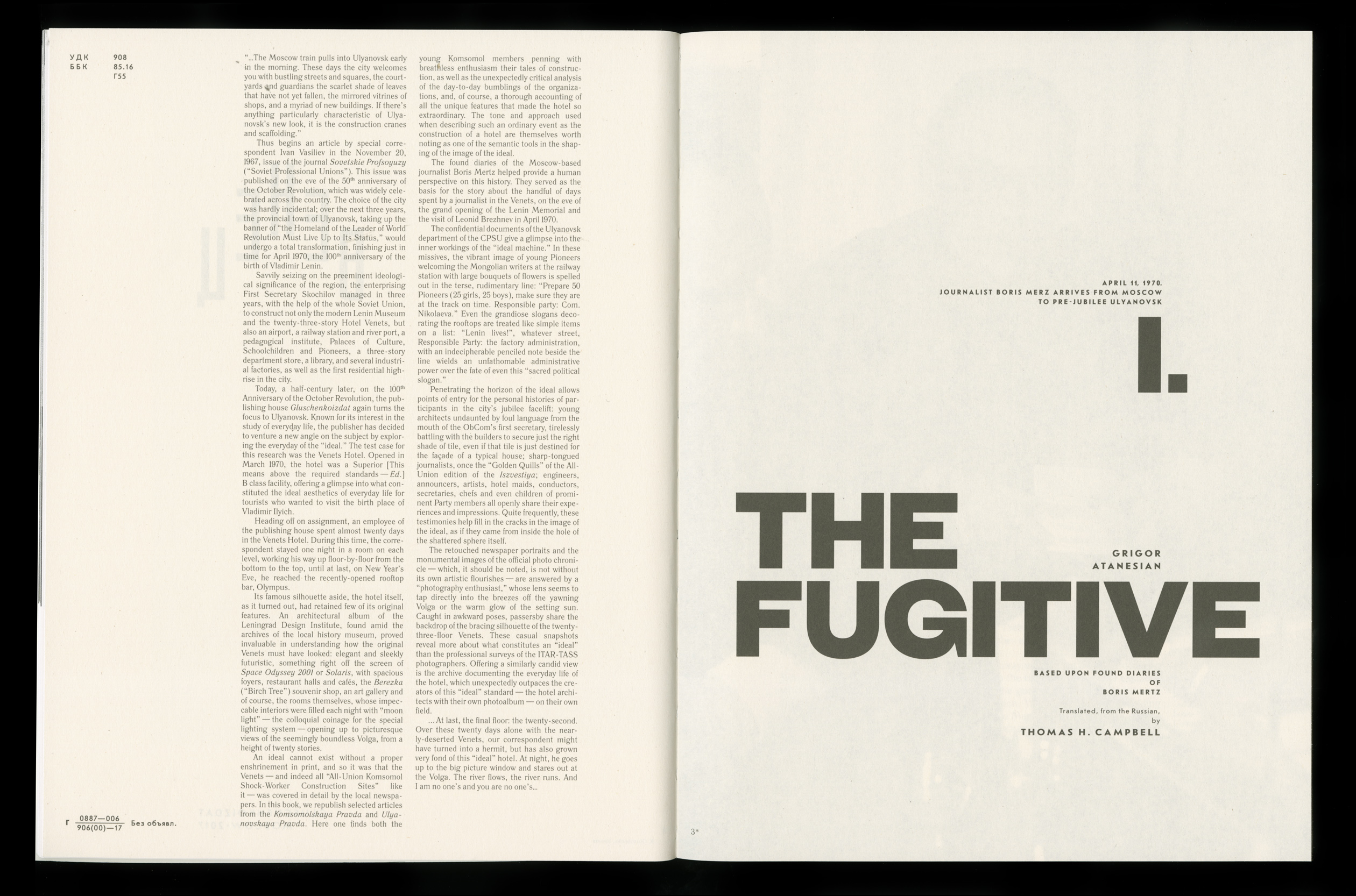

Thus begins an article by special correspondent Ivan Vasiliev in the November 20, 1967, issue of the journal Sovetskie Profsoyuzy (“Soviet Professional Unions”). This issue was published on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, which was widely celebrated across the country. The choice of the city was hardly incidental; over the next three years, the provincial town of Ulyanovsk, taking up the banner of “the Homeland of the Leader of World Revolution Must Live Up to Its Status,” would undergo a total transformation, finishing just in time for April 1970, the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Lenin.

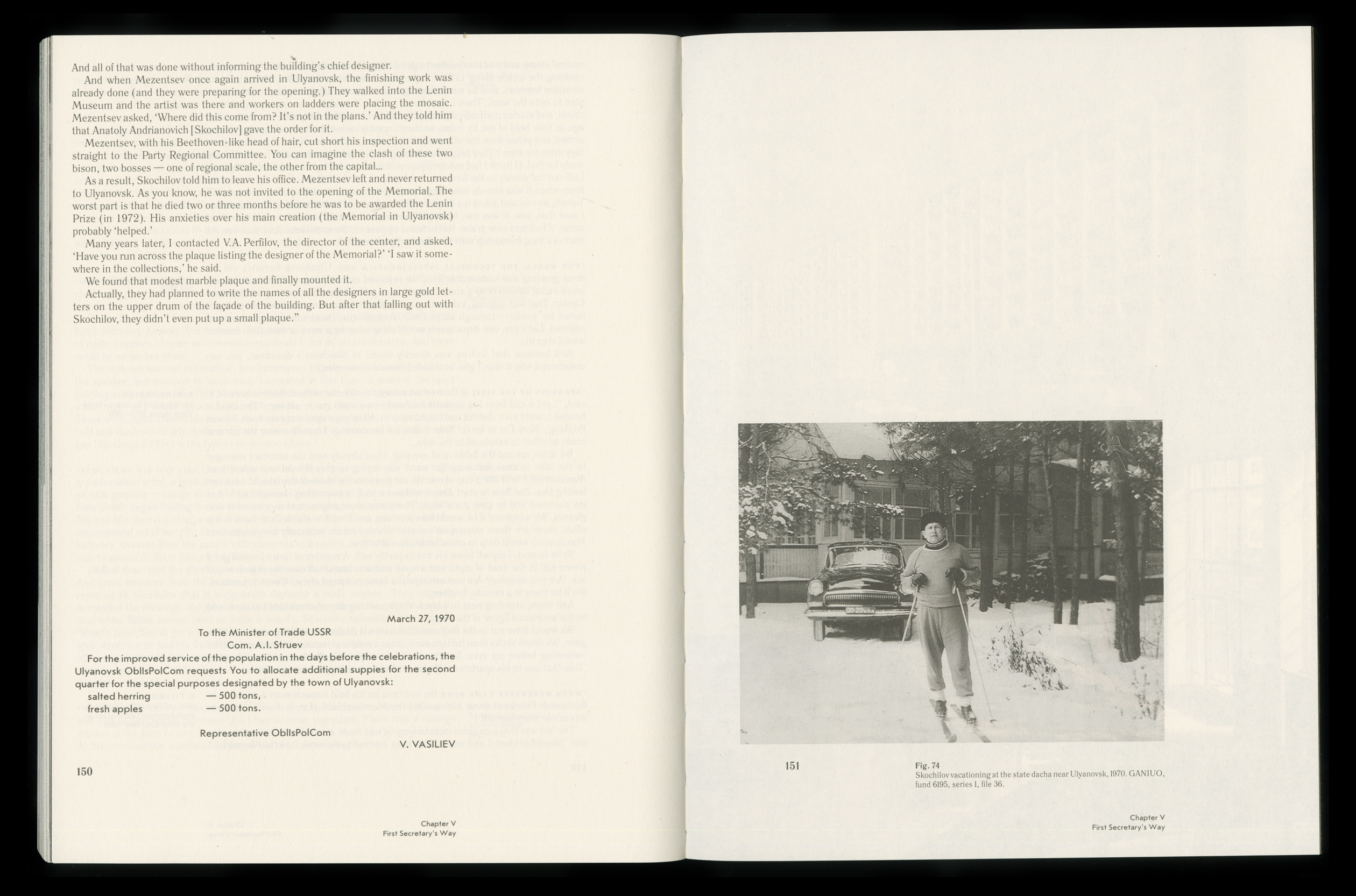

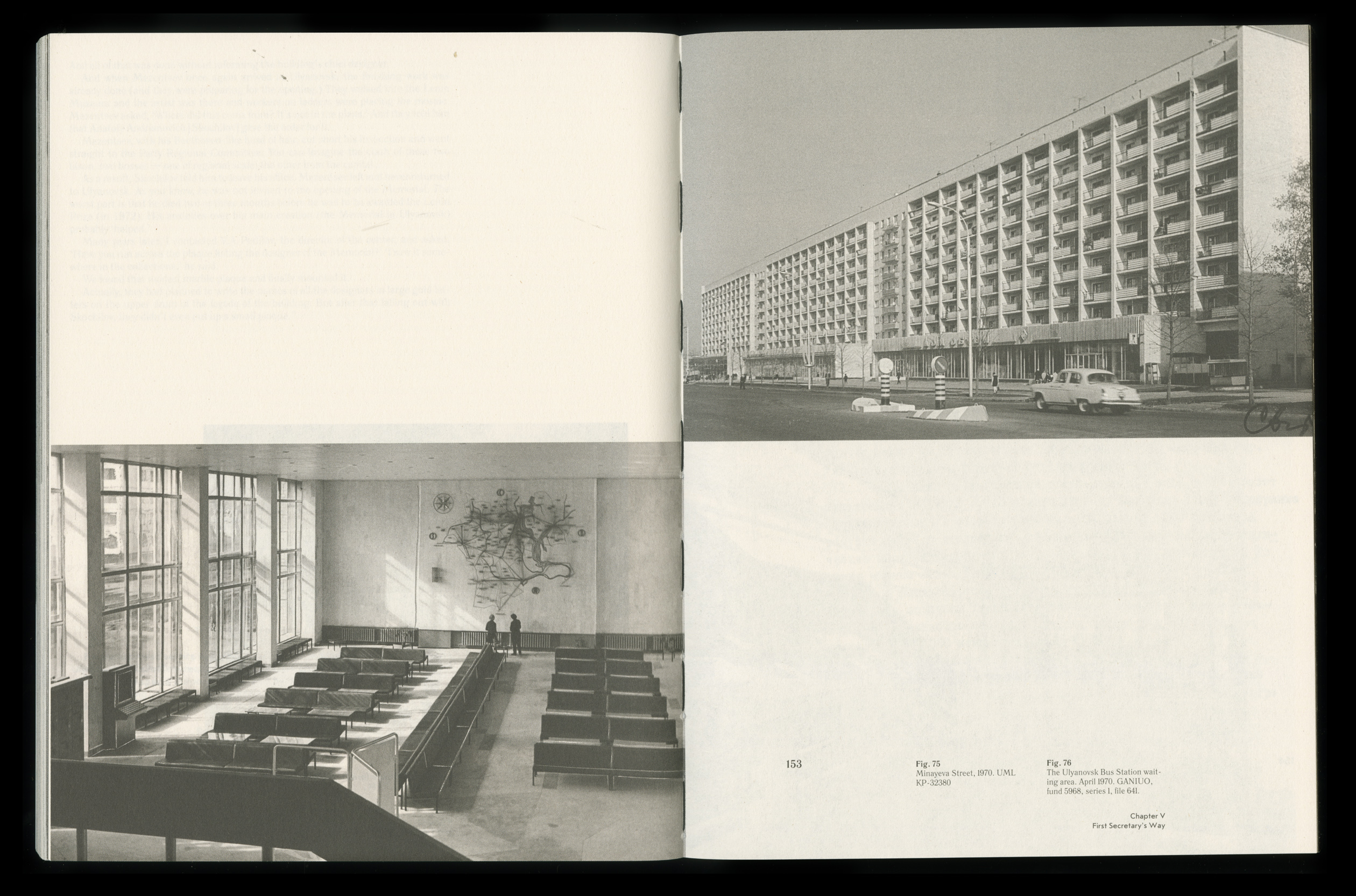

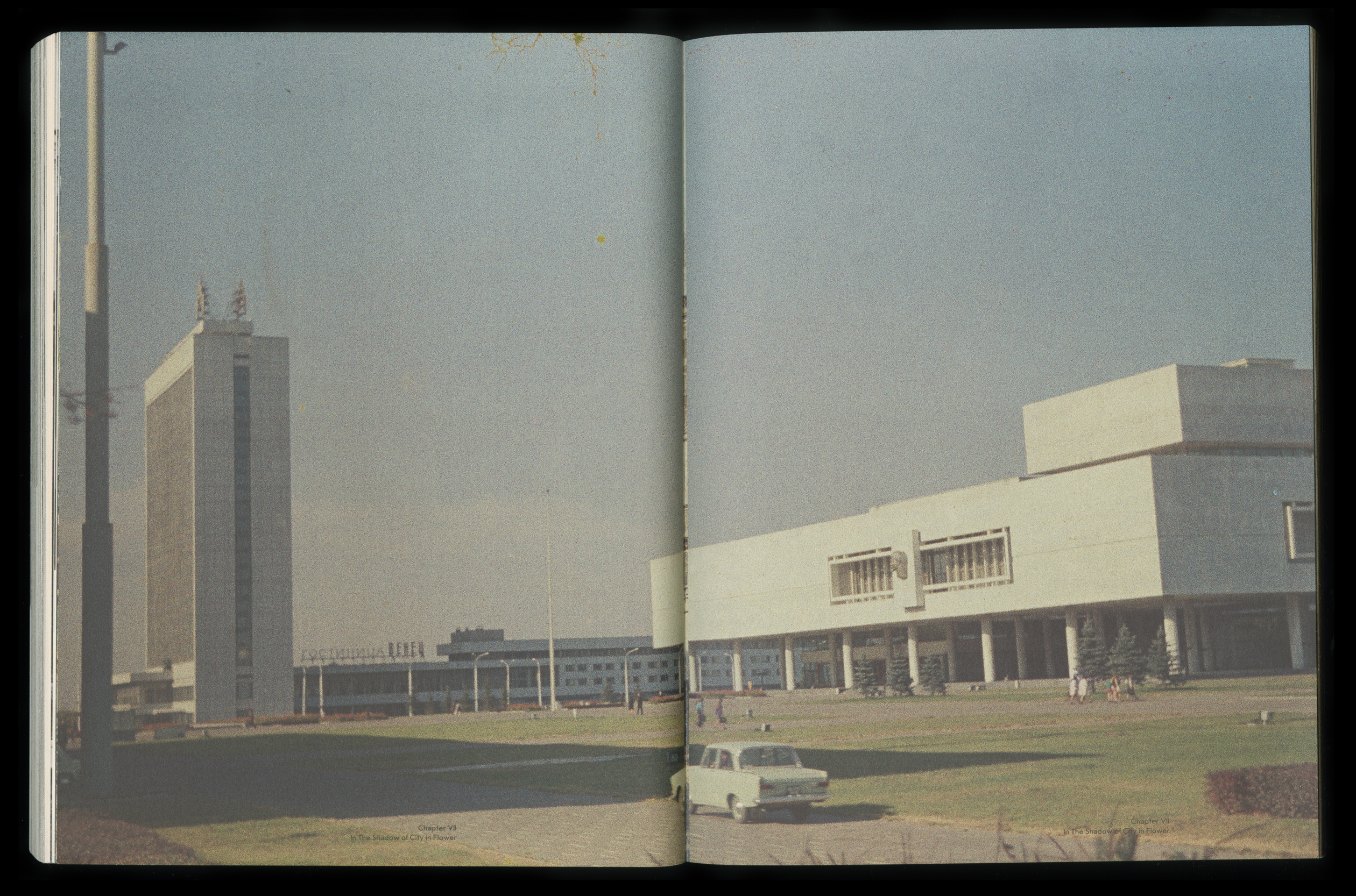

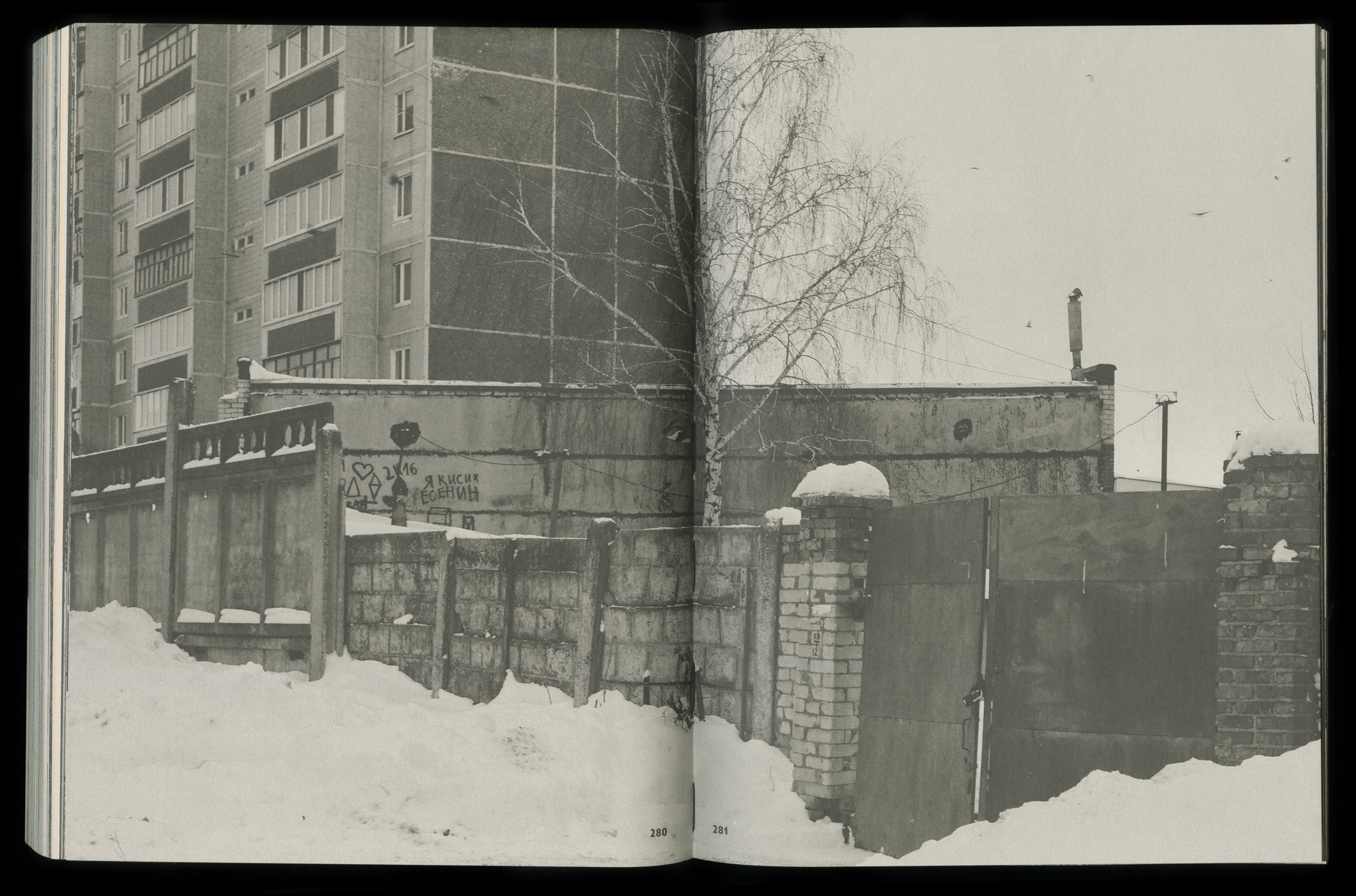

Savvily seizing on the preeminent ideological significance of the region, the enterprising First Secretary Skochilov managed in three years, with the help of the whole Soviet Union, to construct not only the modern Lenin Museum and the twenty-three-story Hotel Venets, but also an airport, a railway station and river port, a pedagogical institute, Palaces of Culture, Schoolchildren and Pioneers, a three-story department store, a library, and several industrial factories, as well as the first residential high-rise in the city.

Today, a half-century later, on the 100th Anniversary of the October Revolution, the publishing house Gluschenkoizdat again turns the focus to Ulyanovsk. Known for its interest in the study of everyday life, the publisher has decided to venture a new angle on the subject by exploring the everyday of the “ideal.” The test case for this research was the Venets Hotel. Opened in March 1970, the hotel was a Superior [This means above the required standards — Ed.] B class facility, offering a glimpse into what constituted the ideal aesthetics of everyday life for tourists who wanted to visit the birth place of Vladimir Ilyich.

Heading off on assignment, an employee of the publishing house spent almost twenty days in the Venets Hotel. During this time, the correspondent stayed one night in a room on each level, working his way up floor-by-floor from the bottom to the top, until at last, on New Year’s Eve, he reached the recently-opened rooftop bar, Olympus.

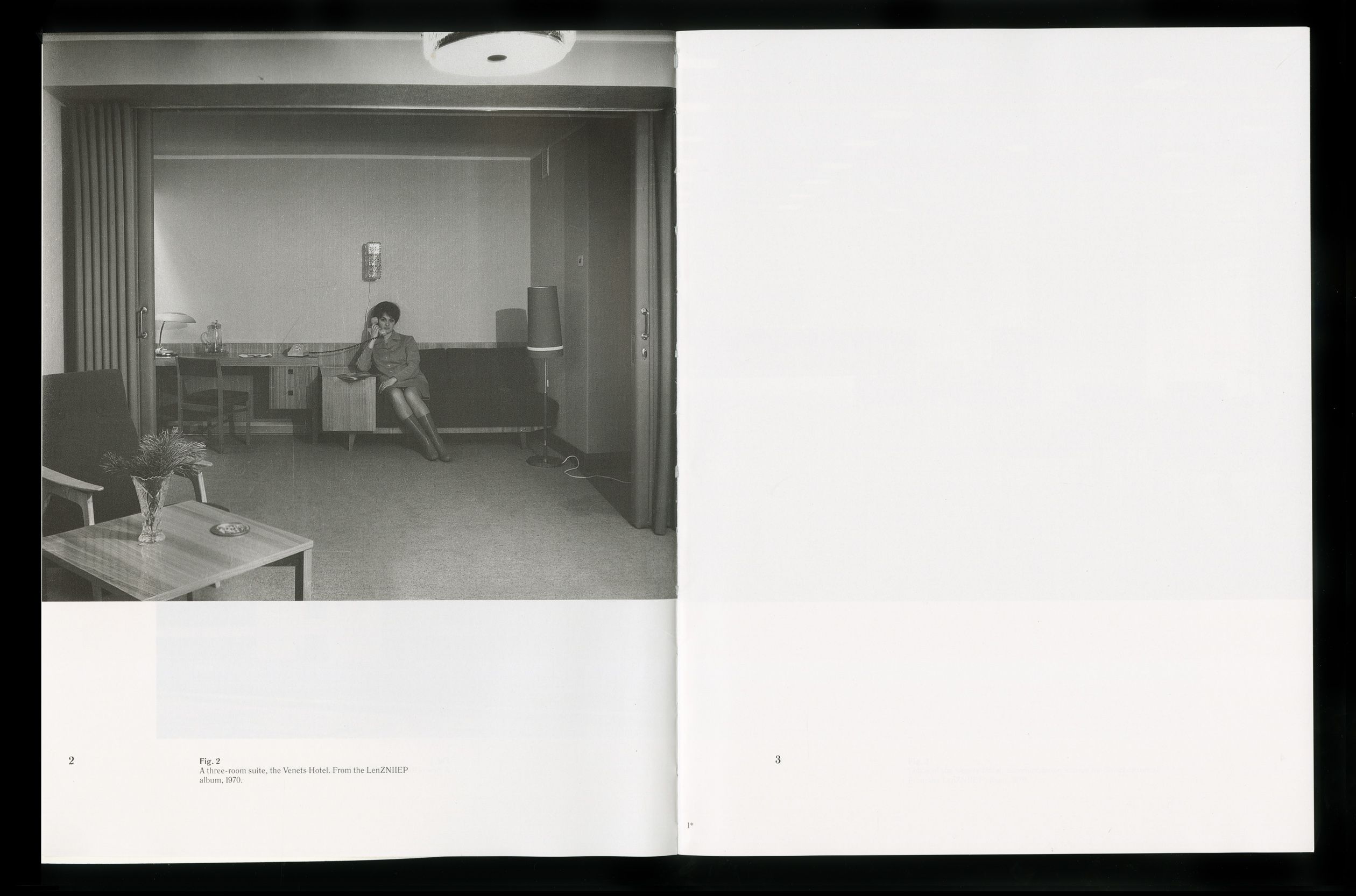

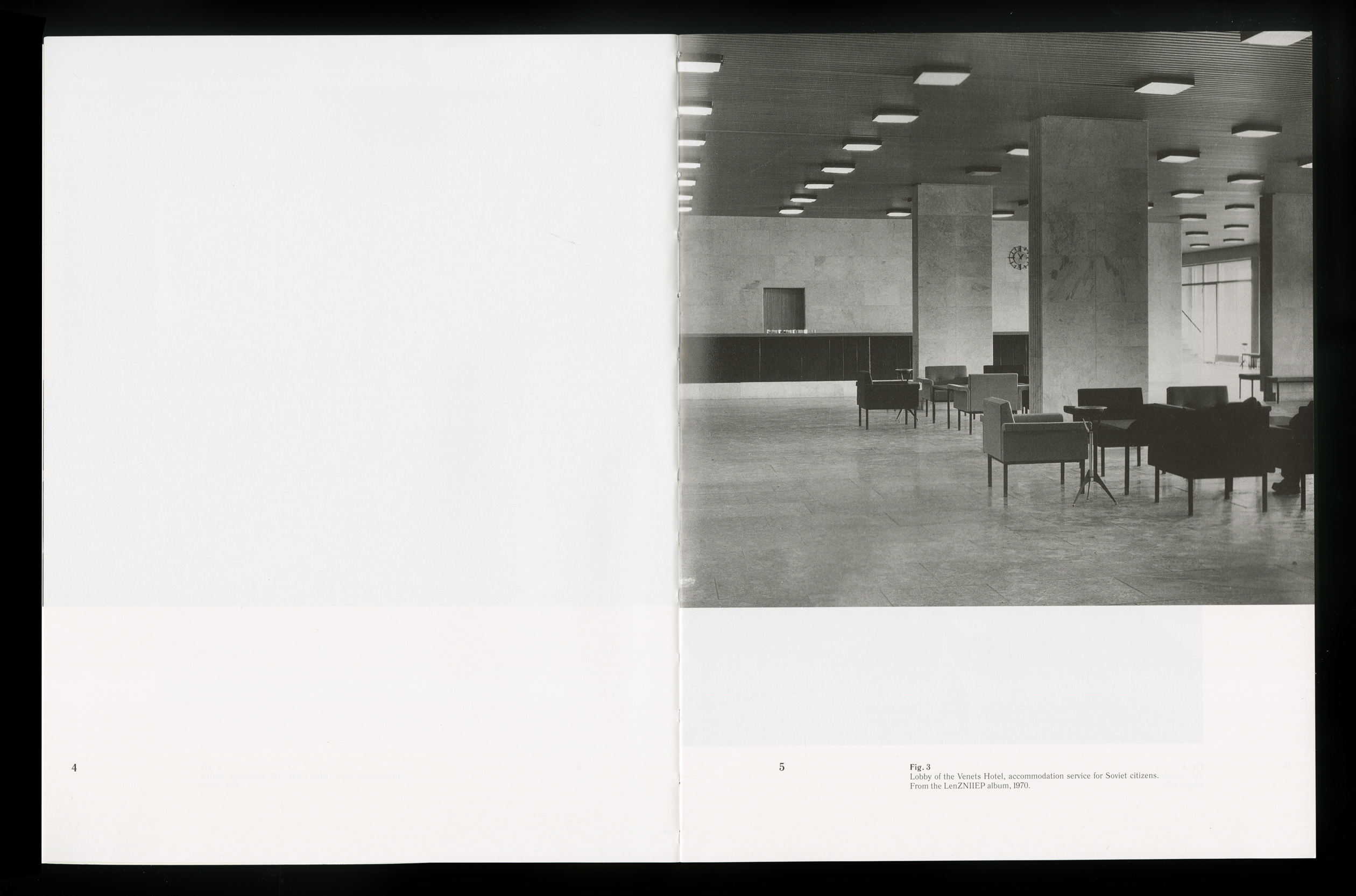

Its famous silhouette aside, the hotel itself, as it turned out, had retained few of its original features. An architectural album of the Leningrad Design Institute, found amid the archives of the local history museum, proved invaluable in understanding how the original Venets must have looked: elegant and sleekly futuristic, something right off the screen of Space Odyssey 2001 or Solaris, with spacious foyers, restaurant halls and cafés, the Berezka (“Birch Tree”) souvenir shop, an art gallery and of course, the rooms themselves, whose impeccable interiors were filled each night with “moon light” — the colloquial coinage for the special lighting system — opening up to picturesque views of the seemingly boundless Volga, from a height of twenty stories.

An ideal cannot exist without a proper enshrinement in print, and so it was that the Venets — and indeed all “All-Union Komsomol Shock-Worker Construction Sites” like it — was covered in detail by the local newspapers. In this book, we republish selected articles from the Komsomolskaya Pravda and Ulyanovskaya Pravda. Here one finds both the young Komsomol members penning with breathless enthusiasm their tales of construction, as well as the unexpectedly critical analysis of the day-to-day bumblings of the organizations, and, of course, a thorough accounting of all the unique features that made the hotel so extraordinary. The tone and approach used when describing such an ordinary event as the construction of a hotel are themselves worth noting as one of the semantic tools in the shaping of the image of the ideal.

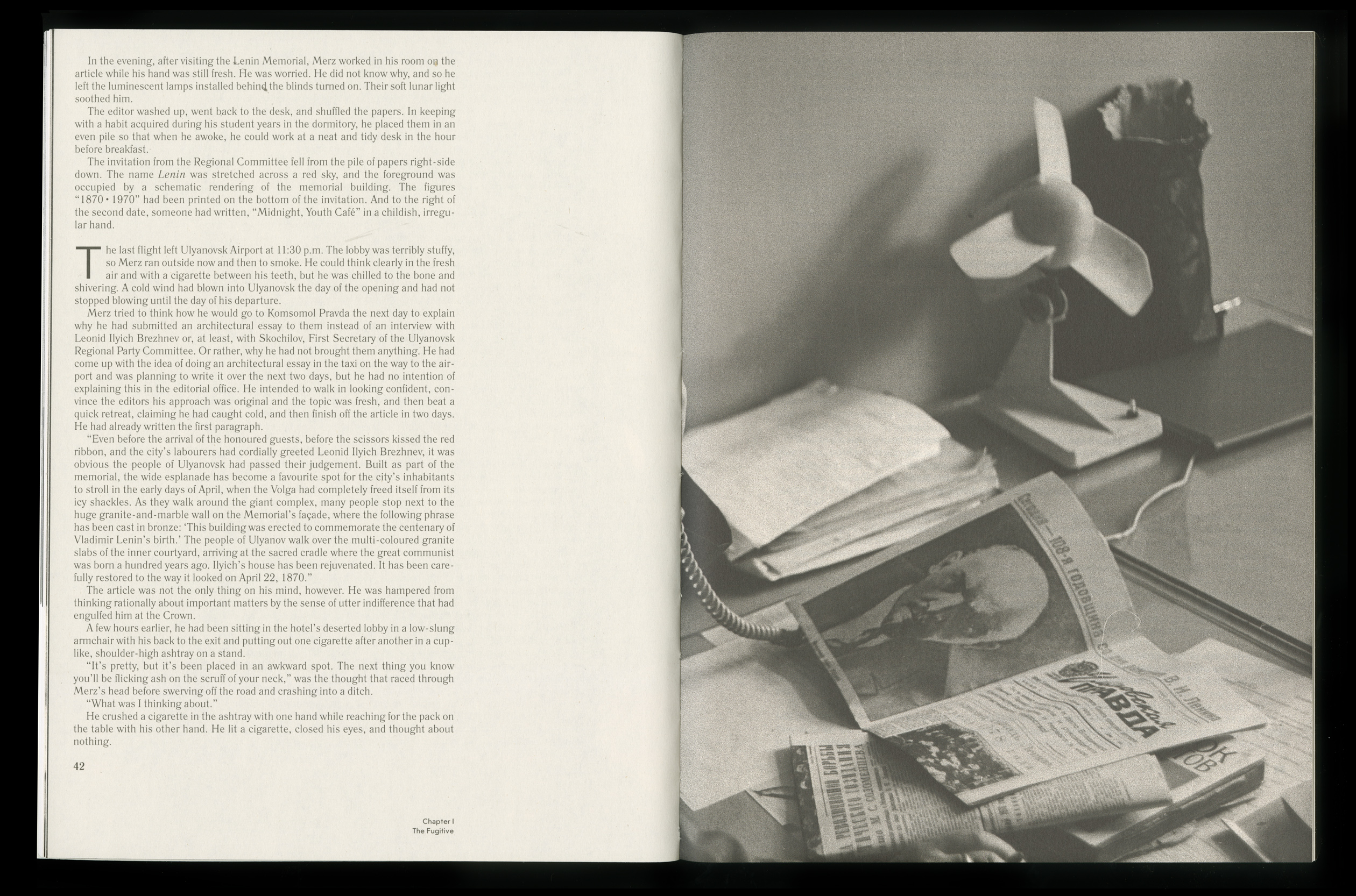

The found diaries of the Moscow-based journalist Boris Mertz helped provide a human perspective on this history. They served as the basis for the story about the handful of days spent by a journalist in the Venets, on the eve of the grand opening of the Lenin Memorial and the visit of Leonid Brezhnev in April 1970.

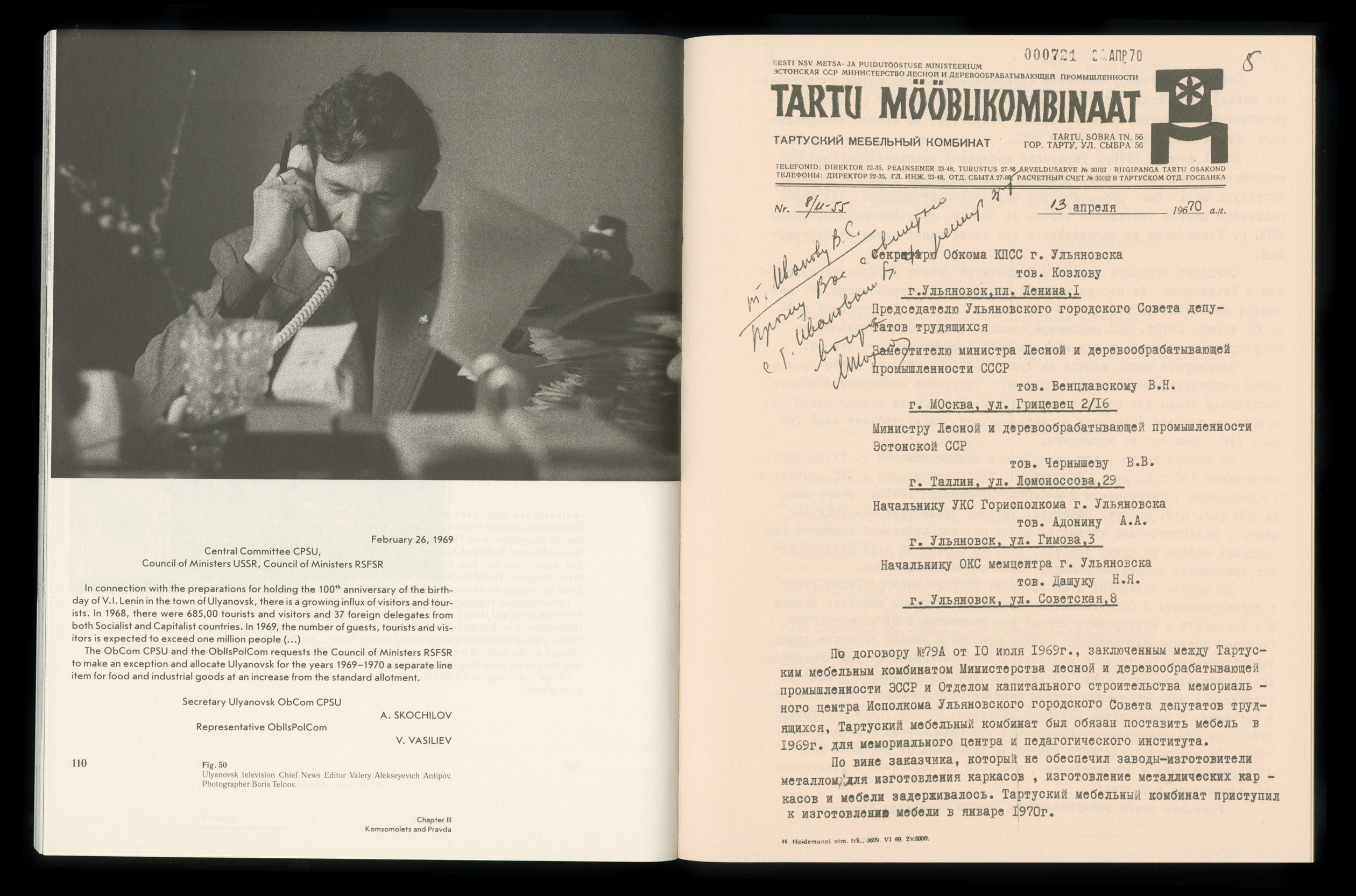

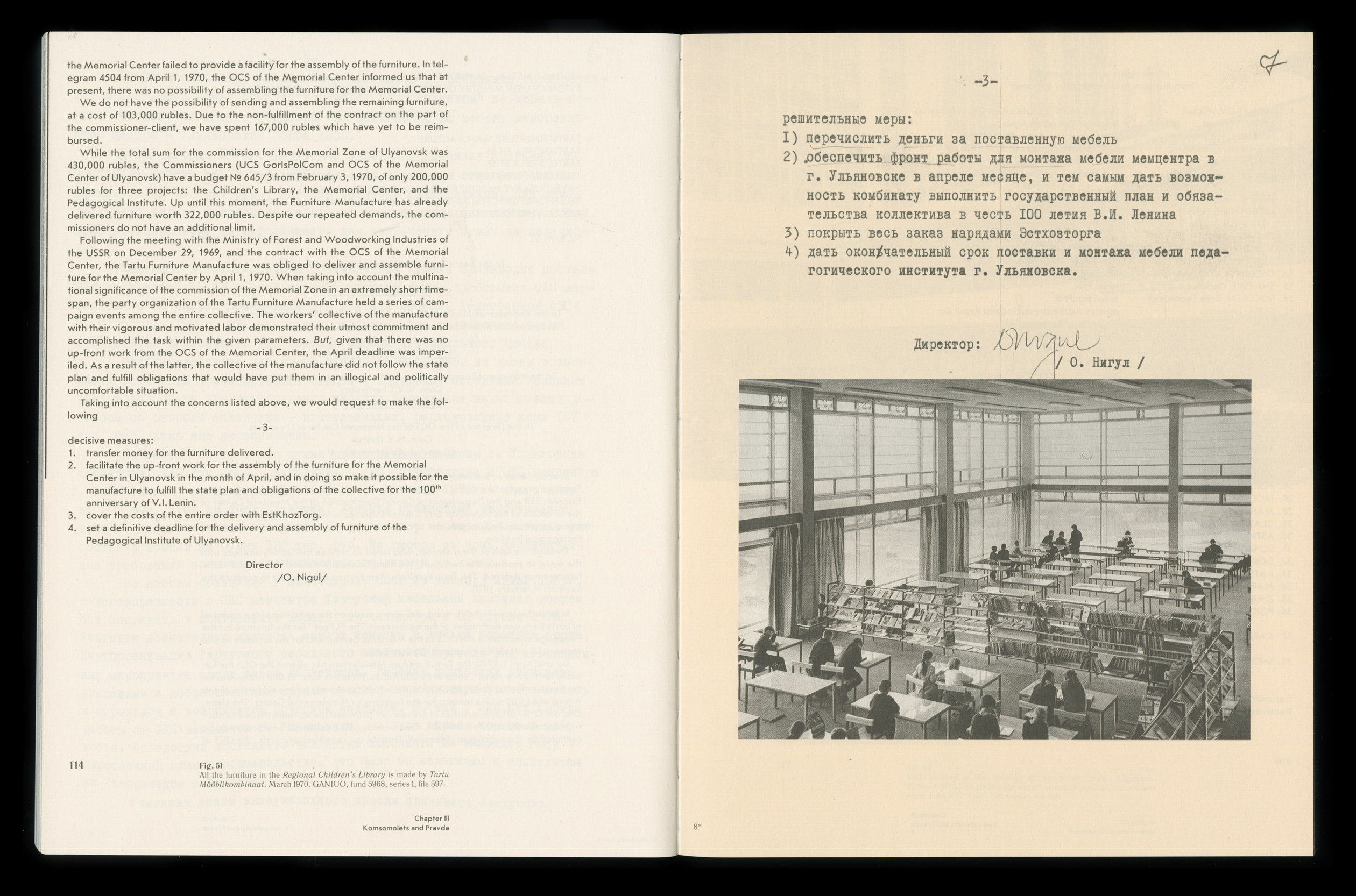

The confidential documents of the Ulyanovsk department of the CPSU give a glimpse into the inner workings of the “ideal machine.” In these missives, the vibrant image of young Pioneers welcoming the Mongolian writers at the railway station with large bouquets of flowers is spelled out in the terse, rudimentary line: “Prepare 50 Pioneers (25 girls, 25 boys), make sure they are at the track on time. Responsible party: Com. Nikolaeva.” Even the grandiose slogans decorating the rooftops are treated like simple items on a list: “Lenin lives!”, whatever street, Responsible Party: the factory administration, with an indecipherable penciled note beside the line wields an unfathomable administrative power over the fate of even this “sacred political slogan.”

Penetrating the horizon of the ideal allows points of entry for the personal histories of participants in the city’s jubilee facelift: young architects undaunted by foul language from the mouth of the ObCom’s first secretary, tirelessly battling with the builders to secure just the right shade of tile, even if that tile is just destined for the façade of a typical house; sharp-tongued journalists, once the “Golden Quills” of the All-Union edition of the Iszvestiya; engineers, announcers, artists, hotel maids, conductors, secretaries, chefs and even children of prominent Party members all openly share their experiences and impressions. Quite frequently, these testimonies help fill in the cracks in the image of the ideal, as if they came from inside the hole of the shattered sphere itself.

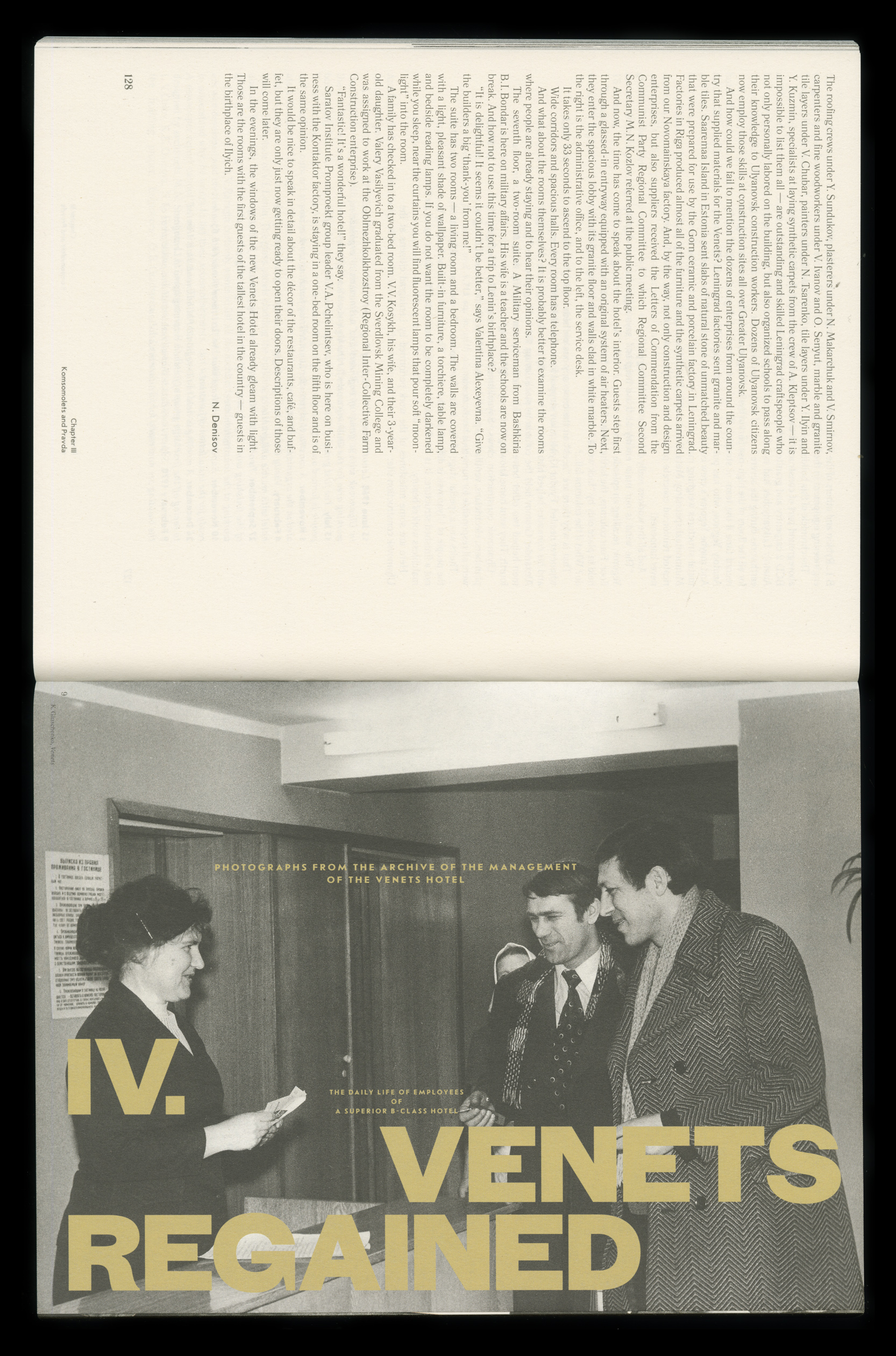

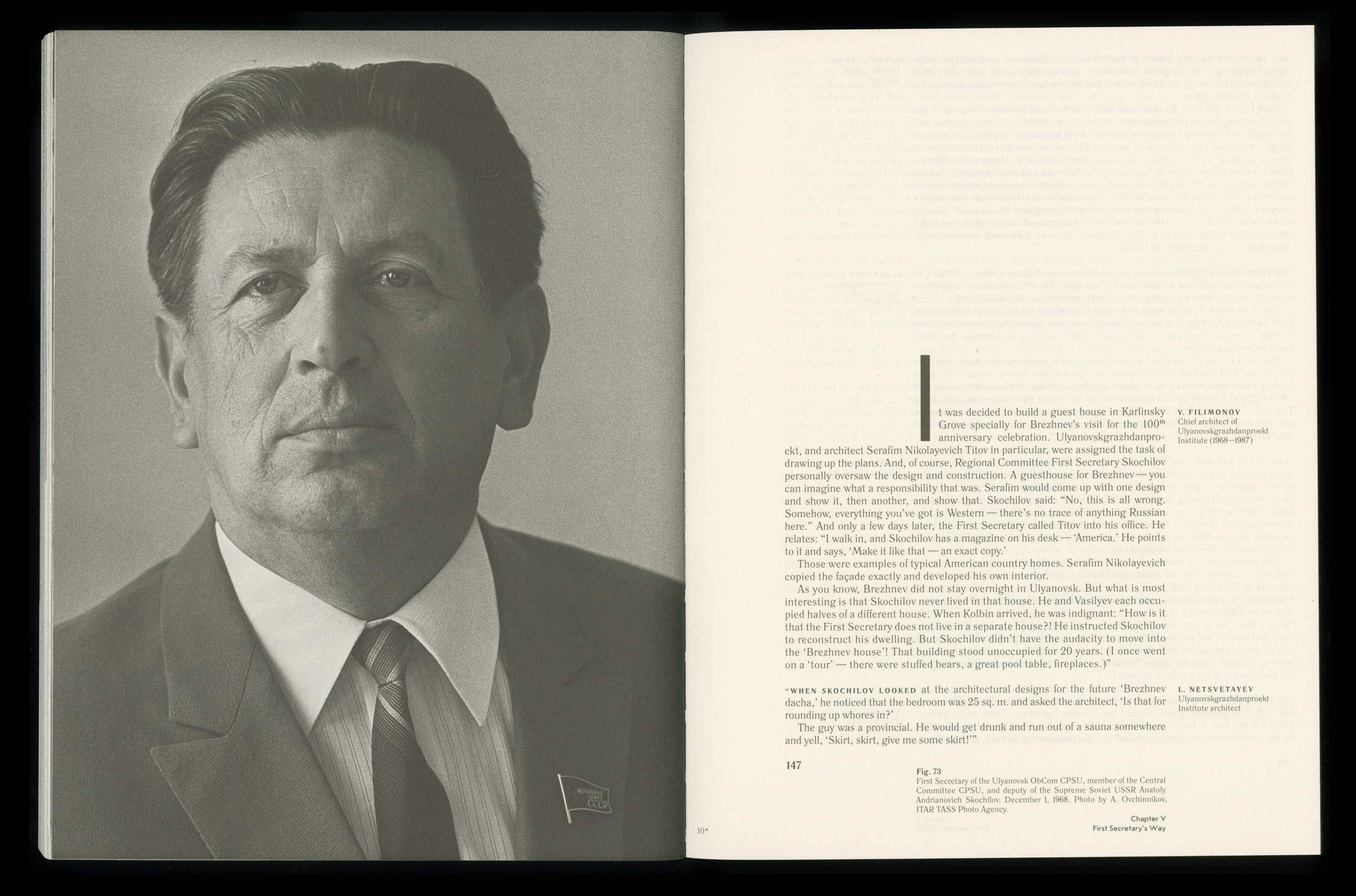

The retouched newspaper portraits and the monumental images of the official photo chronicle — which, it should be noted, is not without its own artistic flourishes — are answered by a “photography enthusiast,” whose lens seems to tap directly into the breezes off the yawning Volga or the warm glow of the setting sun. Caught in awkward poses, passersby share the backdrop of the bracing silhouette of the twenty-three-floor Venets. These casual snapshots reveal more about what constitutes an “ideal” than the professional surveys of the ITAR-TASS photographers. Offering a similarly candid view is the archive documenting the everyday life of the hotel, which unexpectedly outpaces the creators of this “ideal” standard — the hotel architects with their own photoalbum — on their own field.

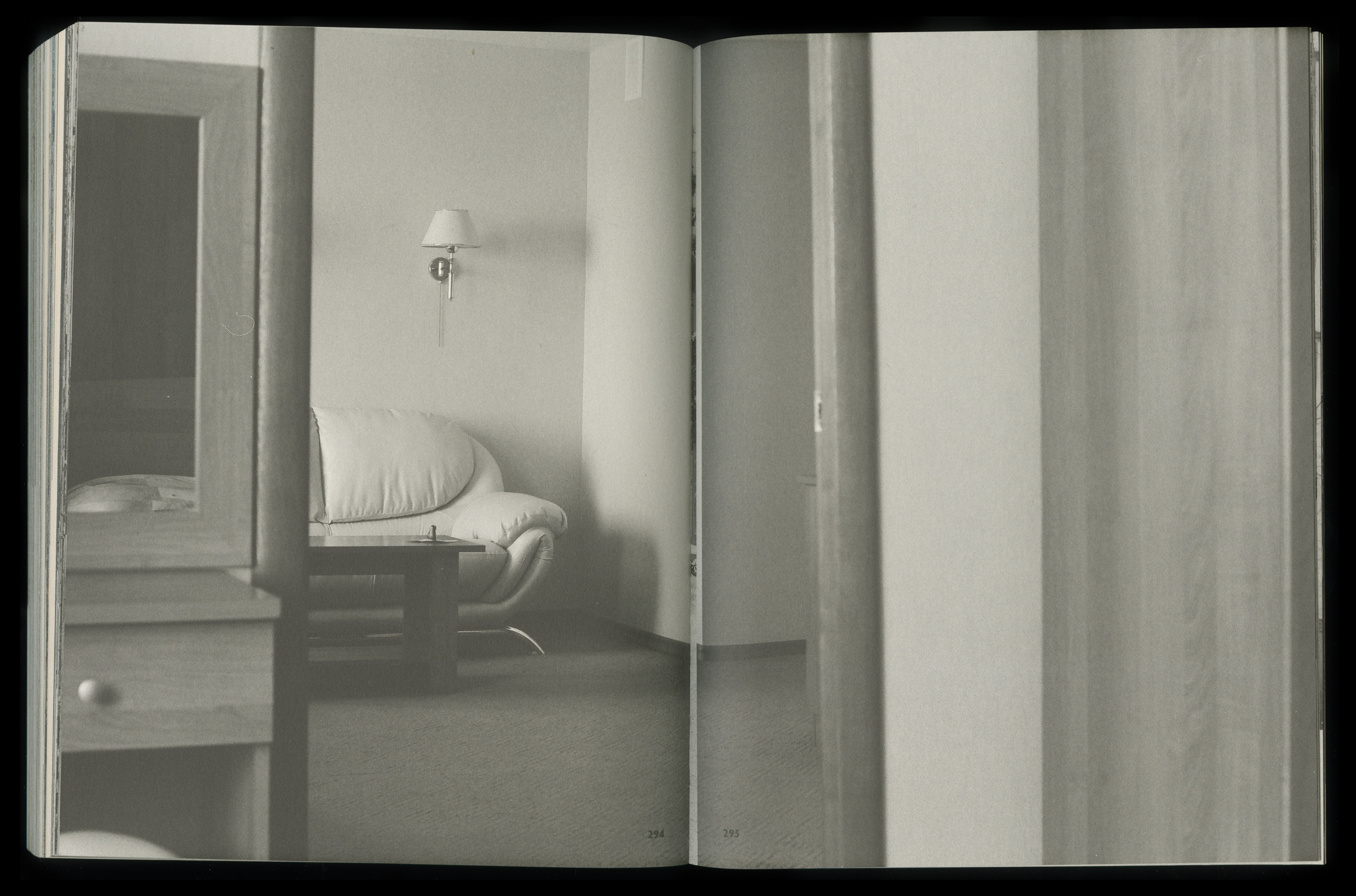

... At last, the final floor: the twenty-second. Over these twenty days alone with the nearly-deserted Venets, our correspondent might have turned into a hermit, but has also grown very fond of this “ideal” hotel. At night, he goes up to the big picture window and stares out at the Volga. The river flows, the river runs. And I am no one’s and you are no one’s…

Thus begins an article by special correspondent Ivan Vasiliev in the November 20, 1967, issue of the journal Sovetskie Profsoyuzy (“Soviet Professional Unions”). This issue was published on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, which was widely celebrated across the country. The choice of the city was hardly incidental; over the next three years, the provincial town of Ulyanovsk, taking up the banner of “the Homeland of the Leader of World Revolution Must Live Up to Its Status,” would undergo a total transformation, finishing just in time for April 1970, the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Lenin.

Savvily seizing on the preeminent ideological significance of the region, the enterprising First Secretary Skochilov managed in three years, with the help of the whole Soviet Union, to construct not only the modern Lenin Museum and the twenty-three-story Hotel Venets, but also an airport, a railway station and river port, a pedagogical institute, Palaces of Culture, Schoolchildren and Pioneers, a three-story department store, a library, and several industrial factories, as well as the first residential high-rise in the city.

Today, a half-century later, on the 100th Anniversary of the October Revolution, the publishing house Gluschenkoizdat again turns the focus to Ulyanovsk. Known for its interest in the study of everyday life, the publisher has decided to venture a new angle on the subject by exploring the everyday of the “ideal.” The test case for this research was the Venets Hotel. Opened in March 1970, the hotel was a Superior [This means above the required standards — Ed.] B class facility, offering a glimpse into what constituted the ideal aesthetics of everyday life for tourists who wanted to visit the birth place of Vladimir Ilyich.

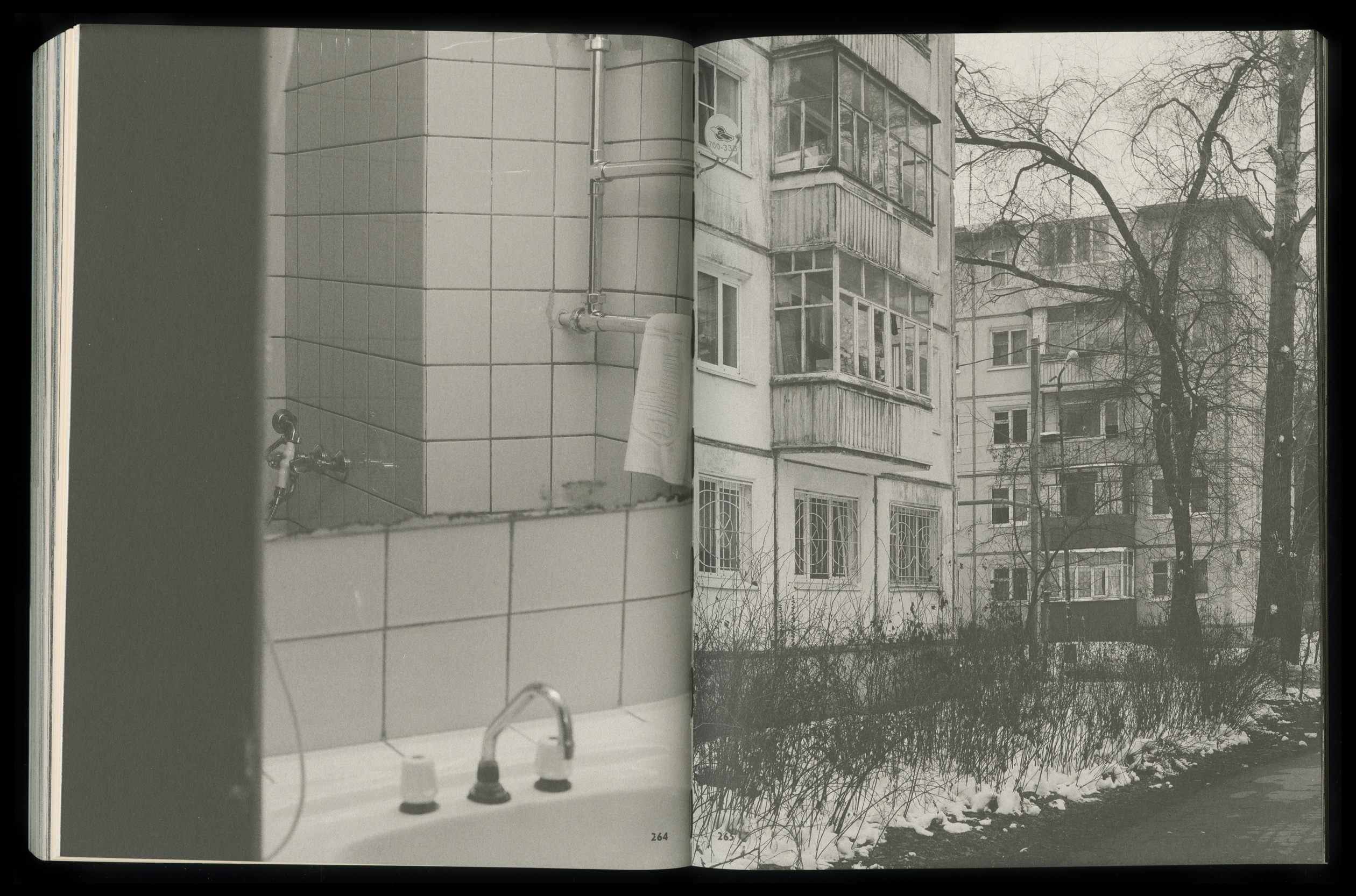

Heading off on assignment, an employee of the publishing house spent almost twenty days in the Venets Hotel. During this time, the correspondent stayed one night in a room on each level, working his way up floor-by-floor from the bottom to the top, until at last, on New Year’s Eve, he reached the recently-opened rooftop bar, Olympus.

Its famous silhouette aside, the hotel itself, as it turned out, had retained few of its original features. An architectural album of the Leningrad Design Institute, found amid the archives of the local history museum, proved invaluable in understanding how the original Venets must have looked: elegant and sleekly futuristic, something right off the screen of Space Odyssey 2001 or Solaris, with spacious foyers, restaurant halls and cafés, the Berezka (“Birch Tree”) souvenir shop, an art gallery and of course, the rooms themselves, whose impeccable interiors were filled each night with “moon light” — the colloquial coinage for the special lighting system — opening up to picturesque views of the seemingly boundless Volga, from a height of twenty stories.

An ideal cannot exist without a proper enshrinement in print, and so it was that the Venets — and indeed all “All-Union Komsomol Shock-Worker Construction Sites” like it — was covered in detail by the local newspapers. In this book, we republish selected articles from the Komsomolskaya Pravda and Ulyanovskaya Pravda. Here one finds both the young Komsomol members penning with breathless enthusiasm their tales of construction, as well as the unexpectedly critical analysis of the day-to-day bumblings of the organizations, and, of course, a thorough accounting of all the unique features that made the hotel so extraordinary. The tone and approach used when describing such an ordinary event as the construction of a hotel are themselves worth noting as one of the semantic tools in the shaping of the image of the ideal.

The found diaries of the Moscow-based journalist Boris Mertz helped provide a human perspective on this history. They served as the basis for the story about the handful of days spent by a journalist in the Venets, on the eve of the grand opening of the Lenin Memorial and the visit of Leonid Brezhnev in April 1970.

The confidential documents of the Ulyanovsk department of the CPSU give a glimpse into the inner workings of the “ideal machine.” In these missives, the vibrant image of young Pioneers welcoming the Mongolian writers at the railway station with large bouquets of flowers is spelled out in the terse, rudimentary line: “Prepare 50 Pioneers (25 girls, 25 boys), make sure they are at the track on time. Responsible party: Com. Nikolaeva.” Even the grandiose slogans decorating the rooftops are treated like simple items on a list: “Lenin lives!”, whatever street, Responsible Party: the factory administration, with an indecipherable penciled note beside the line wields an unfathomable administrative power over the fate of even this “sacred political slogan.”

Penetrating the horizon of the ideal allows points of entry for the personal histories of participants in the city’s jubilee facelift: young architects undaunted by foul language from the mouth of the ObCom’s first secretary, tirelessly battling with the builders to secure just the right shade of tile, even if that tile is just destined for the façade of a typical house; sharp-tongued journalists, once the “Golden Quills” of the All-Union edition of the Iszvestiya; engineers, announcers, artists, hotel maids, conductors, secretaries, chefs and even children of prominent Party members all openly share their experiences and impressions. Quite frequently, these testimonies help fill in the cracks in the image of the ideal, as if they came from inside the hole of the shattered sphere itself.

The retouched newspaper portraits and the monumental images of the official photo chronicle — which, it should be noted, is not without its own artistic flourishes — are answered by a “photography enthusiast,” whose lens seems to tap directly into the breezes off the yawning Volga or the warm glow of the setting sun. Caught in awkward poses, passersby share the backdrop of the bracing silhouette of the twenty-three-floor Venets. These casual snapshots reveal more about what constitutes an “ideal” than the professional surveys of the ITAR-TASS photographers. Offering a similarly candid view is the archive documenting the everyday life of the hotel, which unexpectedly outpaces the creators of this “ideal” standard — the hotel architects with their own photoalbum — on their own field.

... At last, the final floor: the twenty-second. Over these twenty days alone with the nearly-deserted Venets, our correspondent might have turned into a hermit, but has also grown very fond of this “ideal” hotel. At night, he goes up to the big picture window and stares out at the Volga. The river flows, the river runs. And I am no one’s and you are no one’s…