2016

Our Days are Rich and Bright (Прекрасен облик наших будней)

Gluschenkoizdat, 3a, Polkovaya str.

Moscow, Russia • Solo show

Gluschenkoizdat, 3a, Polkovaya str.

Moscow, Russia • Solo show

2021

‘Kirill Gluschenko’s Installation Project

The Beautiful Countenance of Our Everyday Life¹:

The Deconstruction of Soviet Utopia in The Individualised Textual Space’

by Jurij Murašov

Professor of Slavic Literature and

General Literary Studies, University of Konstanz

Fragments from the book by Jurij Murašov,

‘Das elektrifizierte Wort’.

Das Radio in der sowjetischen Kultur der 1920er und 30er Jahre

Wilhelm Fink/Brill • 2021

The Beautiful Countenance of Our Everyday Life¹:

The Deconstruction of Soviet Utopia in The Individualised Textual Space’

by Jurij Murašov

Professor of Slavic Literature and

General Literary Studies, University of Konstanz

Fragments from the book by Jurij Murašov,

‘Das elektrifizierte Wort’.

Das Radio in der sowjetischen Kultur der 1920er und 30er Jahre

Wilhelm Fink/Brill • 2021

¹ Jurij Murašov’s translation of the exhibition title ‘Прекрасен облик наших будней’. Since title originally comes from book ‘Unser Tag hat ein gutes gesicht’ by Karl-Heinz Böhle which had a Russian and an English editions, we decided to use those translations: ‘Our Days are Rich and Bright’ and ‘Прекрасен облик наших будней’.

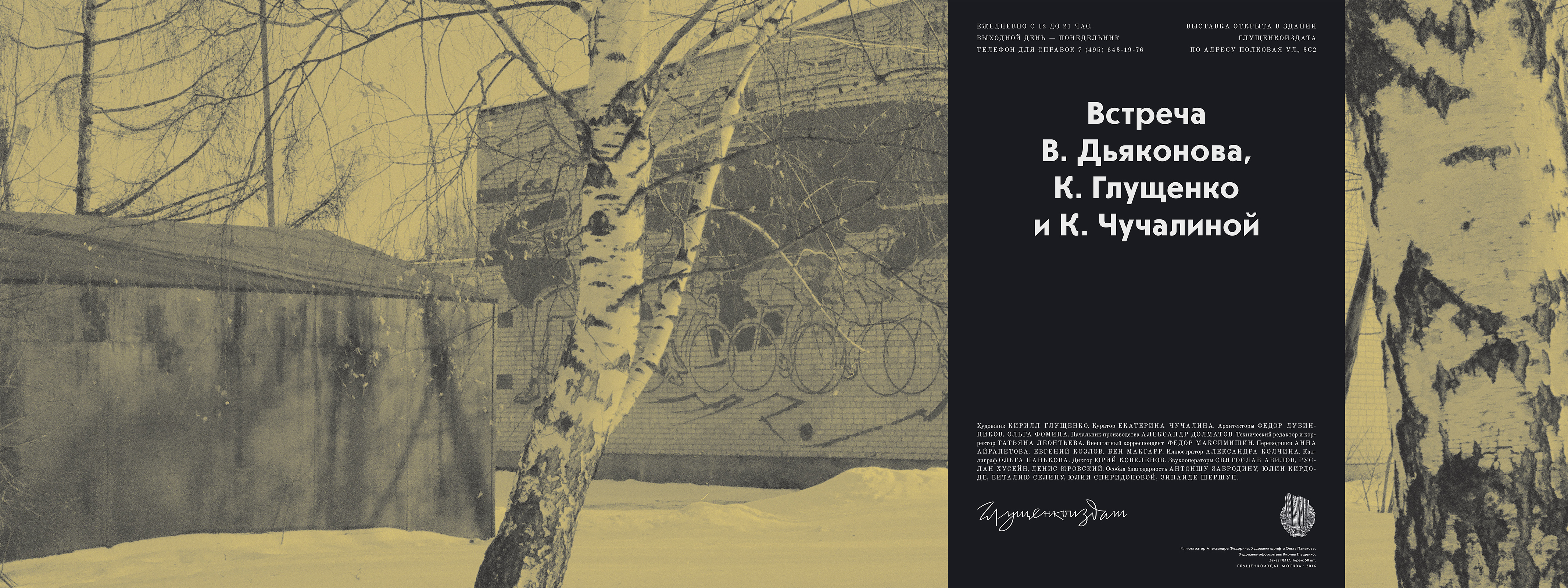

The installation “The Beautiful Countenance of Our Everyday Life” presents itself as a project of the Gluschenkoizdat press. This peculiar name for a publishing house, in which the artist’s name is combined with the common abbreviation for Soviet publishers, “izdat” (from “izdatel’stvo”, Engl. “press”), points to the project’s concept: imitating while simultaneously breaking with Soviet forms and techniques of representation.

On the one hand, the exhibition, in its entire “visual manifestation” (“vizual’nyj obraz”) and its acoustic presentation, bears witness to the bureaucratic logic of publishing work and the technical, graphic and rhetorical methods of a Soviet state press of the 1950s and 1960s. In order to reproduce the atmosphere of a Soviet company, the installation project was realised not in a museum but in a former factory. The spatial arrangements and the furniture reflect Soviet design of the 1950s; the era is also suggested by the original and remade electro-acoustic devices. The Gluschenkoizdat publication projects on display reproduce the Soviet book but also other typographic products such as postcards and posters or record sleeves. The design applies not only to the fonts, colours, layout and technical production (e.g. the binding) of the printed matter, but also to the code numbers and chiffres indicating the stages of the manufacturing process and the bureaucratic and ideological procedures of control and approval. In this respect, Gluschenko employs the artistic technique of appropriation.

On the other hand, the project represents an ironic distancing and the restitution of individual experience vis-à-vis the Soviet conscious with its myth of the “beautiful countenance of our everyday life”. This is achieved via minimal “displacements” (“sdvigi”) and disruptions in the visual and acoustic self-representation of the Soviet utopian culture. Examples of this ploy are the lettering and logo of Gluschenkoizdat. The lettering is taken from the title page of a Soviet book on Old Russian cities for the neon “Gluschenkoizdat” sign on the building’s facade and the individual city book projects inside the exhibition.

On the one hand, the exhibition, in its entire “visual manifestation” (“vizual’nyj obraz”) and its acoustic presentation, bears witness to the bureaucratic logic of publishing work and the technical, graphic and rhetorical methods of a Soviet state press of the 1950s and 1960s. In order to reproduce the atmosphere of a Soviet company, the installation project was realised not in a museum but in a former factory. The spatial arrangements and the furniture reflect Soviet design of the 1950s; the era is also suggested by the original and remade electro-acoustic devices. The Gluschenkoizdat publication projects on display reproduce the Soviet book but also other typographic products such as postcards and posters or record sleeves. The design applies not only to the fonts, colours, layout and technical production (e.g. the binding) of the printed matter, but also to the code numbers and chiffres indicating the stages of the manufacturing process and the bureaucratic and ideological procedures of control and approval. In this respect, Gluschenko employs the artistic technique of appropriation.

On the other hand, the project represents an ironic distancing and the restitution of individual experience vis-à-vis the Soviet conscious with its myth of the “beautiful countenance of our everyday life”. This is achieved via minimal “displacements” (“sdvigi”) and disruptions in the visual and acoustic self-representation of the Soviet utopian culture. Examples of this ploy are the lettering and logo of Gluschenkoizdat. The lettering is taken from the title page of a Soviet book on Old Russian cities for the neon “Gluschenkoizdat” sign on the building’s facade and the individual city book projects inside the exhibition.

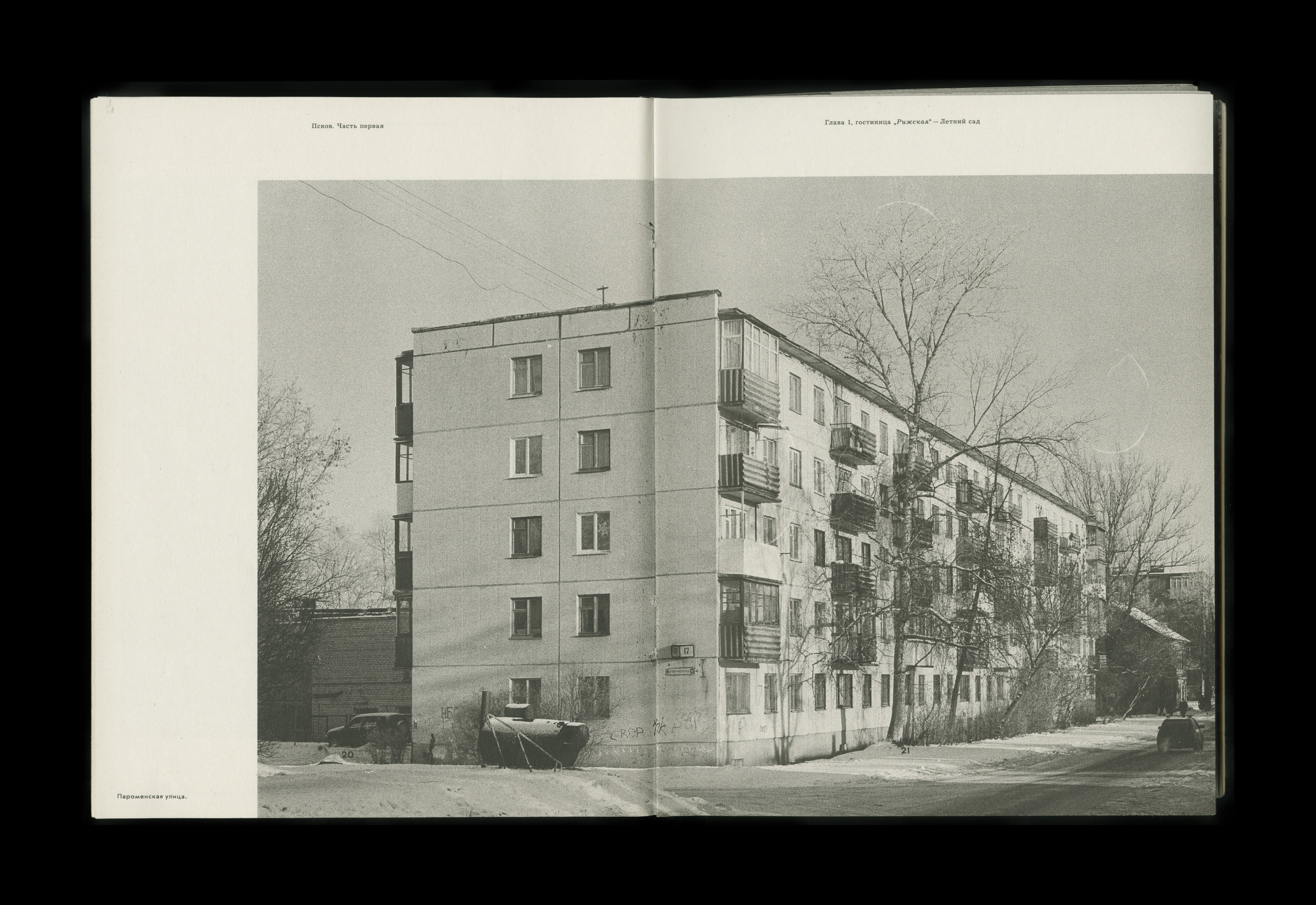

Fig. 3

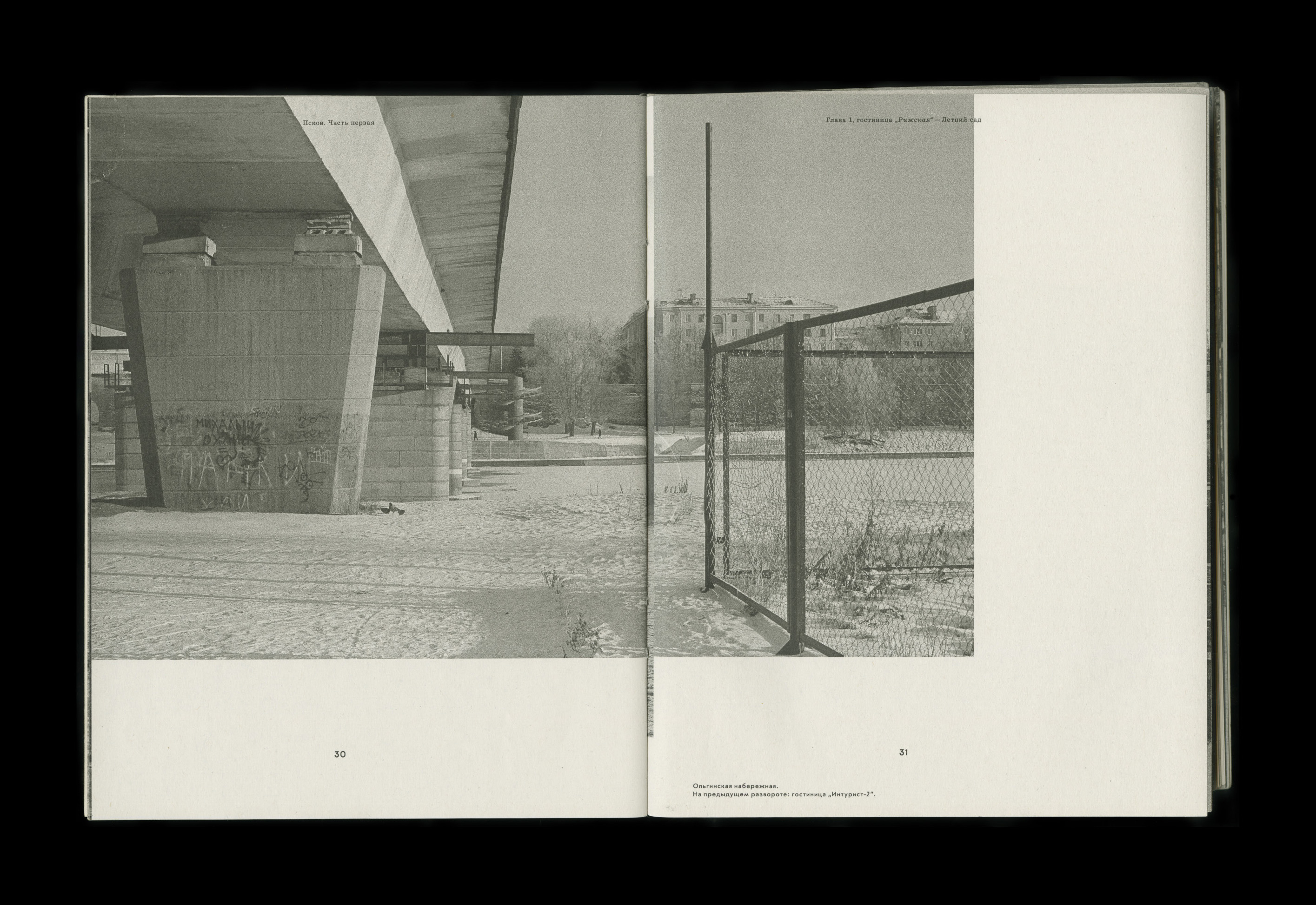

The books present events from “business trips” undertaken by the artist (or a colleague he entrusted with the task) exploring the former Soviet cityscapes with their everyday spaces, the housing and factory complexes, streets and parks, which are documented using original Soviet cameras. The formal features of the series of pictures reproduces Soviet photographic design. At the same time, the “beautiful countenance of our everyday life” proves to be a promise without any visible or empirical basis when heavy clouds of smoke hang over the city in a morning haze (fig. 4) or the empty, snow-covered meadows on the banks of a river are bridged by bulky, ugly steel and concrete (fig. 5). The human element is banished from the pictures of these urban scenes or reduced to a mere hint in the form of a lit window in a large black housing block (figs. 6-7). When human figures are featured, they appear marginalised (fig. 8) or as crooked shapes scurrying away from the rays of the winter sun (fig. 9).

← Fig. 4–7 →

← Fig. 8-9 →

While the series of photographs show the “beautiful countenance of our everyday life” as spaces devoid of the human element, the accompanying texts focus on personal experience and everyday details. These include small biographical sketches of the artist himself, such as the short text “Baba Masha” in the book on Pskov. Here the narrator remembers visiting his grandmother as a child; a strange acquaintance of Baba Masha’s lived in the neighbourhood in a spooky “giant, black, crooked house” that seemed to him like “a hole frozen in the air” and which he approached “always with fear” when he had to go there to fetch “salt or something” for his grandmother. Behind the high wooden fence, everything was “dirty and confined”; “the bath house, chicken coop, shed, awnings and the house itself huddled into a compact pile”. Even when the boy spent time visiting Baba Masha with his grandmother, he felt uneasy at the way the old women fried black rissoles, washed down with homemade vodka and Baba Masha, pointing to a portrait, “always remembered how beautiful she once was, often crying when she was drunk”. The scene culminates with the boy stealing into the tiny, gloomy bedroom, where he turns on the television, on which “after a few minutes a picture slowly starts to form from thin, running lines”. As in Erik Bulatov’s famous soc art picture of 1982/85 Television (Televidenie), here too it is the Soviet news programme Vremja that appears on the screen, but its reports of successes and optimism about the future remain ineffective and produce merely sleepiness instead of socialist enthusiasm: “The speaker’s droning voice crawled slowly from the speakers. Straining, I stared into the screen and tried to understand his speech while the room gradually sank in a thick, almost tangible murmur. […] Time dragged on slowly, and my eyes began to close all by themselves.”

Fig. 10

The private and the individual permeating the dark texts of the city books is ultimately the focus of another, separate project by Gluschenkoizdat: the publication Nikolaj Kozakov, Diary (Dvevnik), 1962. Moscow 2016 (fig. 11).

This production is based on a folder of notes found during an ethnographic excursion undertaken by colleagues of the artist. The folder contained diaries meticulously kept by Nikolaj Nikolaevič Kozakov (born in Moscow in 1932, died in 2005 in Zaprudnoe) from the age of fifteen onwards. In 1962, the manuscript was made available to the publishing house, which transcribed it, prepared it for printing and ultimately published it as a book with a run of 1,000 copies. On the publication’s end paper, the publisher expressed “its hope” that these diaries that have been lying in a personal archive for many years and did not have a chance of being published in the times of the Goskomizdat (State Committee of the Council of Ministers of the USSR for Publishing, Printing and the Book Trade—ed.) will find their reader today. Reading these literary-historical documents should help [the reader] understand this “everyday life of ours”. But it should also represent effective inoculation against a nostalgic perception of the photo albums and postcards handed down to us with the smiling faces of factory workers and the splendorous emptiness of grand boulevards before daybreak.

This production is based on a folder of notes found during an ethnographic excursion undertaken by colleagues of the artist. The folder contained diaries meticulously kept by Nikolaj Nikolaevič Kozakov (born in Moscow in 1932, died in 2005 in Zaprudnoe) from the age of fifteen onwards. In 1962, the manuscript was made available to the publishing house, which transcribed it, prepared it for printing and ultimately published it as a book with a run of 1,000 copies. On the publication’s end paper, the publisher expressed “its hope” that these diaries that have been lying in a personal archive for many years and did not have a chance of being published in the times of the Goskomizdat (State Committee of the Council of Ministers of the USSR for Publishing, Printing and the Book Trade—ed.) will find their reader today. Reading these literary-historical documents should help [the reader] understand this “everyday life of ours”. But it should also represent effective inoculation against a nostalgic perception of the photo albums and postcards handed down to us with the smiling faces of factory workers and the splendorous emptiness of grand boulevards before daybreak.

← Fig. 11-12 →

On its own rack next the stands for the city books, the historical authenticity of the figure of Nikolaj Kozakov is reinforced by photographic material from his estate. This question of authenticity is as intricate as it is ultimately of secondary importance for the structure and pragmatics of the diary text. For it is this state of limbo between reality and fiction that represents a constitutive element of Gluschenko’s installation operating on the borderline between documentary reproduction and artistic variation and reinvention.

The key to Gluschenko’s typographic project The Beautiful Countenance of Our Everyday Life is that Kozakov’s diary is presented as an “audio image” (“radiospektakl’”) in the form of a record that can be played in listening booths. These listening booths form the centrepiece of the entire exhibition, both spatially and conceptually (figs. 13–14).

The key to Gluschenko’s typographic project The Beautiful Countenance of Our Everyday Life is that Kozakov’s diary is presented as an “audio image” (“radiospektakl’”) in the form of a record that can be played in listening booths. These listening booths form the centrepiece of the entire exhibition, both spatially and conceptually (figs. 13–14).

← Fig. 13-14 →

This dispersion of the Soviet utopian conscious and acousmatic poetics via the process of Kozakov’s diary entries in a private, intimate and individual space full of idiosyncrasies is presented as an acoustic experience, at once both refined and comical, in the listening booths. For like the appropriation of Soviet design and layout in the city books, Gluschenko has had Kozakov’s diary read out by a professional radio (and TV) announcer in the markedly impersonal style typical of the Soviet culture of public speaking. As in the typographical part of the installation project, here too there is a clear tension between the private and the personal (the diary) and the self-presentation of the Soviet, which now also tries to maintain the “beautiful countenance of our everyday life”. And even more markedly than in the city books, the impersonal style of official public speaking clearly attempts to preserve the utopian promise of the Soviet against Kozakov’s idiosyncratic self- and writing experiences — at the very moment the impersonal speaker’s voice (involuntarily) slips into mimetic mode via Kozakov’s stubborn narration. Just as the affirmation of the self via the writing process subverts the utopian conscious into idiosyncratic experiences, it makes itself heard in the acoustic and acousmatic space of Soviet power. This occurs not via an ideological counter-position, but via the change in tonality and in the way in which language, voice and writing react to each other and the world.

← Fig. 15-16 →

If Moscow conceptualism deconstructs and parodies the Soviet utopian conscious and the ideological system via “subversive affirmation”, then Gluschenko rather makes use of the techniques of appropriation, assimilation, reproduction and reduplication. While the conceptualists semiologically subvert the Soviet in their various formations and in various artistic genres, by shifting and reinterpreting Soviet chiffres and codes, Gluschenko — within the boundaries of the semantic — works mediologically, technologically and aisthetically in order to set in motion a contrary dynamic. On the one hand, this shows how the Soviet-utopian is produced by the “beautiful countenance of our everyday life” using specific media constellations, while on other hand it makes clear how, in the very interplay of these media, spaces of individuation and the private can be (re-)opened. In a sense, one could say that Gluschenko’s installation project The Beautiful Countenance of Our Everyday Life deconstructs the Soviet utopian conscious, while at the same time its optimism is appropriated by the restitution of trust in writing’s potential for individuation and reflection. This new trust in writing also distinguishes Gluschenko’s project from Moscow Conceptualism’s artistic treatment of Soviet culture.

← Fig. 17-18 →

Press release

Curated by: Katerina Chuchalina

Venue: Polkovaya Street 3, Moscow, Russia

Dates: 29 April — 3 July 2016

Opening: 28 April, from 7pm

The V–A–C foundation is proud to present the first solo show for Moscow based artist Kirill Glushchenko, entitled Our Days are Rich and Bright. The exhibition is curated by V–A–C’s Head Curator Katerina Chuchalina.

Venue: Polkovaya Street 3, Moscow, Russia

Dates: 29 April — 3 July 2016

Opening: 28 April, from 7pm

The V–A–C foundation is proud to present the first solo show for Moscow based artist Kirill Glushchenko, entitled Our Days are Rich and Bright. The exhibition is curated by V–A–C’s Head Curator Katerina Chuchalina.

Born in Kaliningrad in 1983, Glushchenko’s work sees him as head of a fictional publishing house called ‘Glushchenkoizdat’, of which he is also the sole employee — a reporter of sorts — who spends his time visiting the towns of the former USSR and Socialist bloc, to write and publish books about them.

Glushchenko’s art takes the form of a book, therefore, and the artist himself says “I love the intimacy that books imply: books are for you alone and give you the feeling that you are being spoken to directly.” By creating a visual and textual narrative of the towns and villages he visits, the artist retraces the Soviet Union and reconstructs the style of books that were published and mass produced in the late Soviet era to promote new construction, social housing and urban planning in large cities. The artist says that he chooses the places he travels to intuitively and tries to evoke soviet reality during his trips as much as possible, taking regional trains and staying at typical Soviet era hotels, for example. Although the book is the final result, the process itself holds much more meaning.

Our Days are Rich and Bright presents a selection of ‘Glushchenkoizdat’ books illustrating the aesthetic legacy of the Soviet era preserved in towns as diverse as Pskov, Dresden, Ulyanovsk, Riga, Pärnu, Tallinn and Tartu. Another work featured in the exhibition is a volume of found diaries belonging to a bus driver named Nikolai Kozakov. Glushchenko has chosen to publish Kozakov’s diary entries from the year 1962 in the form of a 600-page book covering his daily routine, his love life as well as anecdotes from everyday encounters. We learn that Kozakov graduated from the Moscow University with the hope of becoming a teacher, something that never materialised due to a speech impediment. The entries reveal both bleak and heart-warming sides to life in Soviet Union. The diary is brought to life in the form of a sound recording played inside custom-made booths, read by a well-known Soviet presenter whose voice is instantly recognisable. The show also features postcards from the towns the artist has visited and 60s style furniture. A sign with the name of the publishing house ‘Glushchenkoizdat’ will also be placed on top of the building for the duration of the show.

For many years in Russia, books were used as a strategic cultural product of the country; a symbol of social status of the owner and of the level of importance of State controlled publishing houses. Book design and the printing industry were reinforced by the State Committee for Publishing in the Soviet Union (Goskomizdat) and multiplied by the library system, collectors and the book trade, producing a clean, pristine product in every respect, reflecting the spirit of the times. Publishing houses once occupied large areas of Moscow but unlike other remnants of Soviet cultural production - libraries, cinemas and museums – the publishing system has almost disappeared, leaving little trace of the names or buildings themselves.

Our Days are Rich and Bright will take place at a former Moscow factory in Polkovaya Street, not far from where the publishing houses ‘Prosveshchenie’ [Enlightenment] and ‘Detskaya Kniga’ [Children's Books] were located. Entry to the exhibition is free of charge and the space will be open everyday from midday to 9pm.

Glushchenko’s art takes the form of a book, therefore, and the artist himself says “I love the intimacy that books imply: books are for you alone and give you the feeling that you are being spoken to directly.” By creating a visual and textual narrative of the towns and villages he visits, the artist retraces the Soviet Union and reconstructs the style of books that were published and mass produced in the late Soviet era to promote new construction, social housing and urban planning in large cities. The artist says that he chooses the places he travels to intuitively and tries to evoke soviet reality during his trips as much as possible, taking regional trains and staying at typical Soviet era hotels, for example. Although the book is the final result, the process itself holds much more meaning.

Our Days are Rich and Bright presents a selection of ‘Glushchenkoizdat’ books illustrating the aesthetic legacy of the Soviet era preserved in towns as diverse as Pskov, Dresden, Ulyanovsk, Riga, Pärnu, Tallinn and Tartu. Another work featured in the exhibition is a volume of found diaries belonging to a bus driver named Nikolai Kozakov. Glushchenko has chosen to publish Kozakov’s diary entries from the year 1962 in the form of a 600-page book covering his daily routine, his love life as well as anecdotes from everyday encounters. We learn that Kozakov graduated from the Moscow University with the hope of becoming a teacher, something that never materialised due to a speech impediment. The entries reveal both bleak and heart-warming sides to life in Soviet Union. The diary is brought to life in the form of a sound recording played inside custom-made booths, read by a well-known Soviet presenter whose voice is instantly recognisable. The show also features postcards from the towns the artist has visited and 60s style furniture. A sign with the name of the publishing house ‘Glushchenkoizdat’ will also be placed on top of the building for the duration of the show.

For many years in Russia, books were used as a strategic cultural product of the country; a symbol of social status of the owner and of the level of importance of State controlled publishing houses. Book design and the printing industry were reinforced by the State Committee for Publishing in the Soviet Union (Goskomizdat) and multiplied by the library system, collectors and the book trade, producing a clean, pristine product in every respect, reflecting the spirit of the times. Publishing houses once occupied large areas of Moscow but unlike other remnants of Soviet cultural production - libraries, cinemas and museums – the publishing system has almost disappeared, leaving little trace of the names or buildings themselves.

Our Days are Rich and Bright will take place at a former Moscow factory in Polkovaya Street, not far from where the publishing houses ‘Prosveshchenie’ [Enlightenment] and ‘Detskaya Kniga’ [Children's Books] were located. Entry to the exhibition is free of charge and the space will be open everyday from midday to 9pm.

Public Talks.

Stroyizdat Press editor and art director

Stroyizdat Press editor and art director

Former employee of Stroyizdat Press, book designer Alexander Grigoriev about the art councils (“khudsovet”), rare Kodak film rolls for freelance photographers and Zhurnalnaya typeface.

Ekaterina Astafieva, former Stroyizdat Press chief editor of the editorial board for ‘Urban planning and architecture’.

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

Fig. 23

Fig. 24

Fig. 25